Spectrum has been part of Ball State University through decades of both victories and devastation within the LGBTQ+ community.

Being established as an organization on campus in 1974, Spectrum was created just five years after the Stonewall riots and one year after APA removed “homosexuality” from its list of mental illness, according to PBS.

Members of Spectrum have witnessed many milestones from the creation of the pride flag through federal legalization of gay marriage and first-time representation by government officials.

Possibly more important, Spectrum has also remained a safe space for students through general societal pressures and limited rights, as well as tragedies like the AIDS epidemic and the Colorado Springs shooting.

Spectrum has cultivated a space for students to work through those hardships and tragedies comfortably and openly as well as celebrate the wins as a community for nearly 50 years.

When the intent to organize form was submitted to the university, the unofficial name was the Muncie Gay Pride Coalition, but before its establishment on campus, the name was changed to the Ball State Gay Alliance (BSGA) and later the Gay Activist Union (GAU).

Gray Clossman was the leading force behind implementing this safe space on campus as the original chairman. He wanted to “educate the mis or uninformed with facts pertaining to homosexuality.”

He doesn’t recall any difficulty with starting the organization, but said looking back, he’s sure they had some guardian angels among university administrators and faculty.

Now, nearly 70 and living in California, he doesn’t remember a lot of details, but he looks back on his contribution to Ball State’s student life fondly.

“Around 1973, there were a couple of tables in the Student Center cafeteria where gays gathered, played cards and talked,” Clossman said. “We thought that students should have more opportunities to meet and to be comfortable in their own skins.”

He said they were aware that other campuses had similar groups, and while they started as a small organization, they “didn’t want to be left behind.”

Their main initiative in the 70s was to talk to and educate other student groups, and some teachers invited them to speak to classes.

“Most of the students in those classes had never thought about queer people as peers. We didn’t encounter opposition or aggression, but instead interest or incredulity, sometimes silence or pity,” Clossman said.

Just four years after it was established, GAU was disbanded for just as long as it had been around before the GAU constitution was revived and the group was reestablished as BSGA in spring 1983.

Two name changes and a few years later, Stephanie Turner was a graduate student at Ball State and involved in the group.

After graduating and accepting a job teaching in the English department in the late '80s, she was asked to be the faculty adviser for what was then the Lesbian and Gay Student Association (LGSA).

By the time Turner joined the organization, some of the issues they were dealing with weren’t at all like Clossman’s experience. They were still speaking to classes, but for a very different reason.

“We were trying to do a lot of HIV, AIDS education. It was a very scary time before AZT, and a lot of people were worried about getting AIDS,” Turner said. We'd go to these classes … and there'd be like four or five of us, and we would have condoms … And it was amazing that they didn't want to touch those condoms. They were like some kind of a cursed thing.”

Earlier in the epidemic in 1981, they referred to the disease as gay-related immune deficiency (GRID). By 1995 AIDS deaths in the U.S. reached an all time high according to the New York City AIDS Memorial.

Turner recalls coworkers joking in front of her about how transferring money to the organization would give them HIV. She remembers them comparing the deadly disease to a game, touching hands and saying, “Tag, you have AIDS.”

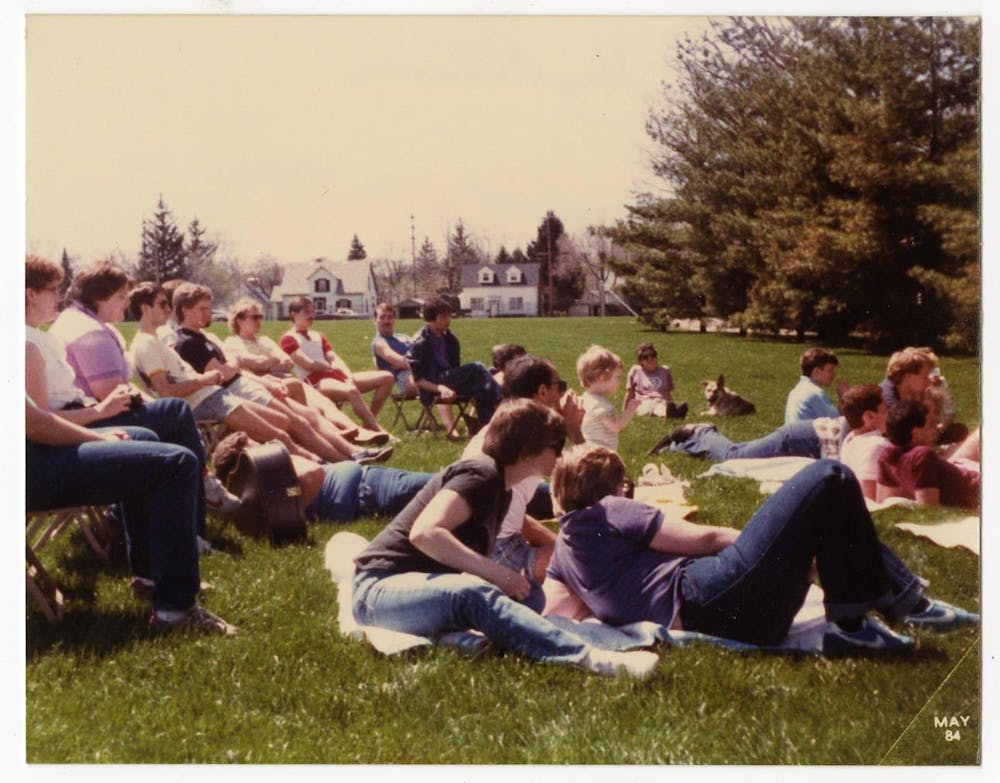

“People were afraid of gay people because of AIDS,” Turner said. “We would have an annual picnic … Oftentimes, somebody would sort of come harass us, so there was harassment, there were pranks, there wasn't violence, but it wasn't very nice.”

In 1990, David Speakman was co-chair at the time and filed a report with Ball State UPD about a sign LGSA had hung up in the Student Center. It was stolen and vandalized with offensive language before being hung back up on the fly swatter.

UPD wrote in the police report that the vandalized banner was returned and suspended any further investigation.

We would try to educate people about what we wanted, which was just to live our lives without harassment and to be recognized as diverse,” Turner said. “We weren't just like one kind of person.

Now, from an outside perspective, Turner recognizes how, just like from Clossman’s time to her’s, the issues and discussion surrounding LGBTQ+ rights has shifted.

Chloee Bowne (left) and Ezra Dalton (right) hug one another after listening to several speakers at a rally against House Bill 1041 Feb. 1, 2022 at University Green. At the time, Dalton was a sophomore at Ball State and the treasurer of Ball State Spectrum. Grace Duerksen, DN

She said looking back they didn’t necessarily have trans issues on their radar in the late 80s and early 90s, but she thinks it’s vital the discussion surrounding trans issues and gender fluidity continues.

“I think that we need to educate people about how important it is to self identify rather than having an identity imposed upon you,” Turner said. “It’s OK to be nonbinary, trans people need support not persecution.”

The landscape for people who have been involved in Spectrum has changed dramatically since its start. Spectrum has been there through many advancements as well as setbacks in the LGBTQ+ community over the years.

In today’s current political landscape, both Clossman and Turner recognize students in organizations like Spectrum have new challenges, but they said they’re glad the community that brought them comfort during hard times is still around.

“Up through the Biden era at least, progress has been tremendous! LGBTQ people have been much more comfortable and secure in their jobs and relationships than formerly. The first LGBTQ student organizations made gays and lesbians visible as classmates, neighbors and colleagues, and as people with families, careers and fun,” Clossman said. “Every era has its own concerns. Ours was simply to be seen at all.”

Spectrum’s roots stem from a small group of students playing cards at a table in the Student Center, but their impact has grown through campus and into the Muncie community since 1974.

Contact Ella Howell via email at ella.howell@bsu.edu.