The building that once stood at 217 N. College Ave. is now a parking lot. There is virtually no hint that a newsroom once stood in its place — no sign that student journalists once walked south down North McKinley Avenue after class to shuffle into a house that was once home to The Ball State Daily News.

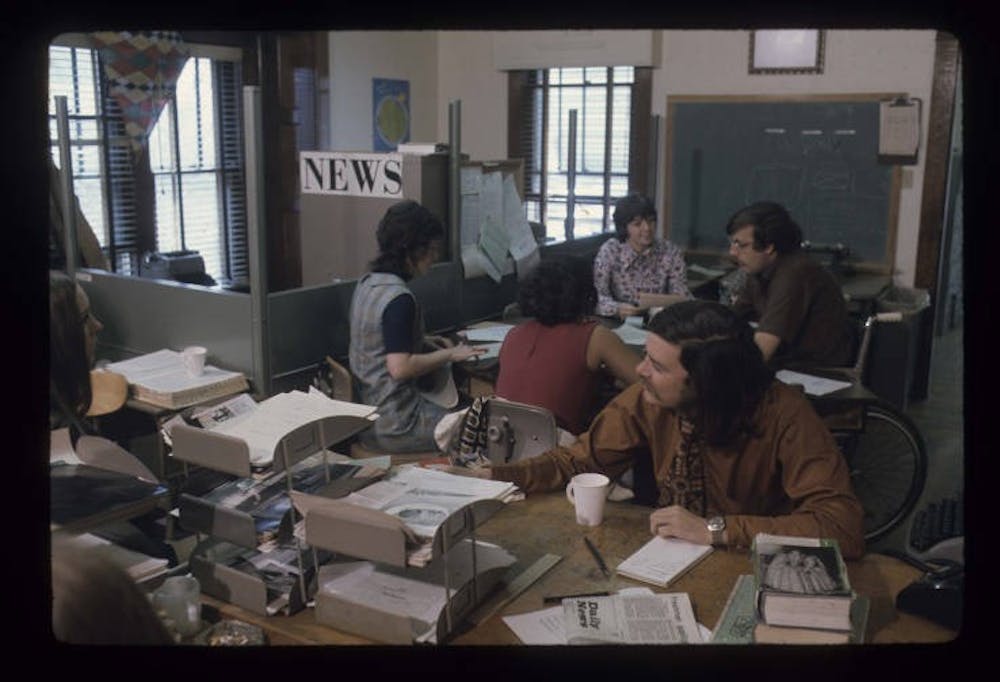

In 1972, as The Daily News was celebrating its 50th anniversary, this house was nothing less than a hub. It would be another five years before its reporters would move into the West Quadrangle Building. It would be another 36 years for the Holden Strategic Communication Center and Unified Media Lab to open on the second floor of the Art and Journalism Building.

This house on the outskirts of campus, south of the L.A. Pittenger Student Center, was the center of life for student journalists at Ball State in 1972. It was here they managed a daily print operation, wrote and learned.

Gene Policinski’s first introduction to The Daily News came when he was hired as a student janitor his freshman year at Ball State in 1968. He was assigned to clean the Daily News Offices in the evening after most of the reporters left. Being a journalism major, he took this opportunity to get to know the professors working in the building, as they would often be there after hours.

Beginning his sophomore year, Policinski started reporting for the paper, eventually becoming the editor-in-chief his senior year. Policinski, now a senior fellow for the Freedom Forum in Washington, D.C., presided over The Daily News during the paper’s semicentennial and spearheaded multiple investigations into the campus and surrounding areas.

“I helped start what was, at that time, called ‘Weekend Magazine,’ which was a tabloid, because I thought we needed a weekly product,” Policinski said. “And while I was there, the staff — not me, but the whole staff — we did a project looking at housing in Muncie … we did a whole investigation on that.”

Policinski also described an investigation on voter registration he helped lead during his time as editor-in-chief. When the 26th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1971, making all 18-year-old citizens eligible to vote, a large percentage of college students across the nation suddenly had a say in the 1972 presidential election.

However, Policinski said, because many politicians in Delaware County didn’t want the “liberal, hippie, radical kids … at Ball State” participating, students were often told they could only register in their home county, despite spending most of their time every year at school.

“We teamed up with a better government organization, and I was one of the people sent in sort of undercover,” Policinski said. “I went in to register and the same thing … I didn’t tell them where, but I said, ‘I work in Hancock County in the summer — I don’t ever go back to St. Joseph [County], really’ … and so they registered [me].”

Following the investigation, the organization The Daily News worked with filed a lawsuit in federal court against the county and won, prompting the Pulitzer Prize Board to send the paper a letter hailing its achievement. To this day, Policinski said he still has a copy of that investigation.

Policinski held his first professional journalism job at The Greenfield Daily Reporter in the summer of 1969, before he entered his sophomore year at Ball State. He went on to work for The Daily Reporter until he graduated, after which he began working for The Chronicle-Tribune in Marion, Indiana. In 1976, he moved to Indianapolis to cover the Indiana Statehouse for Gannett News Service, leading him to eventually move to Washington, D.C., in 1979 to cover national politics for the same company.

In 1982, Policinski became a founding editor of the Gannett-owned USA Today, staying in Washington. His run with USA Today ended in 1996, his seventh year as managing sports editor. Today, Policinski said he still considers himself to be a journalist because he continues to write columns for the Freedom Forum, a nonprofit organization that advocates for First Amendment rights.

Throughout his long career as a journalist, Policinski has worked in print, audio, video and online media. Therefore, Policinski said he realizes the ever-growing importance of a wide media skill set among today’s journalists, even if such a range of abilities wasn’t necessarily important in the 20th century.

“I think, up until recently, radio, television weren't really blended in the way I would’ve hoped with [Ball State’s] CCIM [College of Communication, Information and Media],” Policinski said. “They sort of grew up separately, so to speak. But the honest truth is it’s all storytelling — and I think that’s … the mechanism, the medium shaped how things were done in terms of getting news and information.”

Stephen Key attended Butler University in Indianapolis from 1973-77, during which time he worked for The Butler Collegian, working his way up to editor-in-chief his senior year. Key, now executive director and general counsel of the Hoosier State Press Association (HSPA), also said there is an increasing reliance on multimedia skills for journalists, as opposed to the print-centric approach of his time.

“In the 1970s, the internet was really not a part of anybody’s life, so we were pretty much putting together a print product and we were done,” Key said. “Now … you’re seeing the need for students to not only be able to write, but to take video or photos with their phone or other equipment — they’re looking to create not only print products but digital products.”

Being editor-in-chief of The Butler Collegian, Key had a unique perspective on the weekly printing process of the paper and others like it. After each print production night, Key would take the pages to The Noblesville Daily Ledger, where the printer created aluminum plates with images of the pages. Through a complicated printing process, the ink from the plates would be transferred to sheets of newsprint, creating the final product.

While Key himself didn’t run the presses, it was his job to stay awake during the process and bring the bundles of paper back to Butler and set them on the campus newsstands.

After college, Key worked for The Daily Ledger and The Daily Journal of Johnson County in Franklin, Indiana. In 1991, he attended the Indiana University School of Law in Indianapolis. Two years later, he became the general counsel at HSPA, a trade association representing newspapers across Indiana by providing legal services.

The HSPA also maintains the Eugene S. Pulliam internship, named for a previous owner of the Indianapolis Star. The name Pulliam has been entwined with journalism in Indiana since the 1930s. Eugene C. Pulliam founded Central Newspapers Inc., a media holding company, in 1934, and famously acquired the Indy Star 10 years later.

A graduate of DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, Eugene C. also helped found Sigma Delta Chi in 1909, a journalism fraternity that later evolved into the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ). The SPJ today provides newspapers across the nation with legal services and has a written code of ethics that details much of the blueprint of ethical decision-making in the industry.

Eugene C.’s son, Eugene S., served in the U.S. Navy during World War II and worked at the Indy Star alongside his father until 1975, when the elder Pulliam died and Eugene S. took on publishing responsibilities until his own death in 1999.

Today, Russell Pulliam, the grandson of Eugene C. and son of Eugene S., is an associate editor of the Indy Star, now owned by Gannett Co. Inc. He writes a weekly column for the paper and is also the director of the Pulliam Journalism Fellowship, a college internship program at the Indy Star and The Arizona Republic in Phoenix. As he presides over an internship emblazoned with his grandfather’s name, Russell has worked to keep his family’s legacy alive.

“My father and my grandfather and I, we started the fellowship as an attempt to try to be a bridge between the classroom and the newsroom — that was our idea,” Russell said. “And back then, my grandfather was worried about losing the best people to television, because back then, you got paid a little better and had the glamor of being on air, and he just thought we needed to keep strong reporters on the writing, print side, too.”

One specific change in the news industry since his father’s and grandfather’s times, Russell said, was the field’s economic focus. While advertisement revenue was often enough for most newspapers to stay afloat in the mid-20th century, Russell said the lack of print ads in recent years has led to the decline of print journalism. This, along with other changes in the industry — such as an increasing reliance on multimedia skills and the importance of the internet — has “pushed [journalists] into an entrepreneurial direction,” Russell said.

“The ones who are entrepreneurial, like some of these guys who start blogs and they take off, or they become specialists in a certain area, they really have it made,” Russell said. “But some others, who are not designed by nature to be entrepreneurs, kind of have a harder time, unless they can land up at The Washington Post.”

As a journalist for more than 50 years, Policinski is aware of the challenges modern journalists face and how they’re different to the ones of the ‘70s. Today, he said, journalists are often seen not as “the ultimate purveyor of truth,” but as a threat to certain narratives people would rather push.

“Being a journalist today is damn tough,” Policinski said. “I will tell you, over the course of my years, it was never easy — but I think it’s tougher today than it’s ever been.”

When Policinski describes his time as editor-in-chief, he often starts with the negatives. He said it was a “huge time suck” that “took hours, hours and hours” and that “you basically gave up your life to do it.”

But he had no shortage of praise for Ball State and its programs either. He commended the early convergence of audio, video, design and print at CCIM, and he’s also served for more than ten years on the CCIM Dean’s Executive Advisory Council.

“I always thought that Ball State maintained that kind of presence that taught you the theory of why but also taught you the practicality,” Policinski said. “And, again, I think they’ve stayed pretty well, over the years, on top of the changes in the industry.”

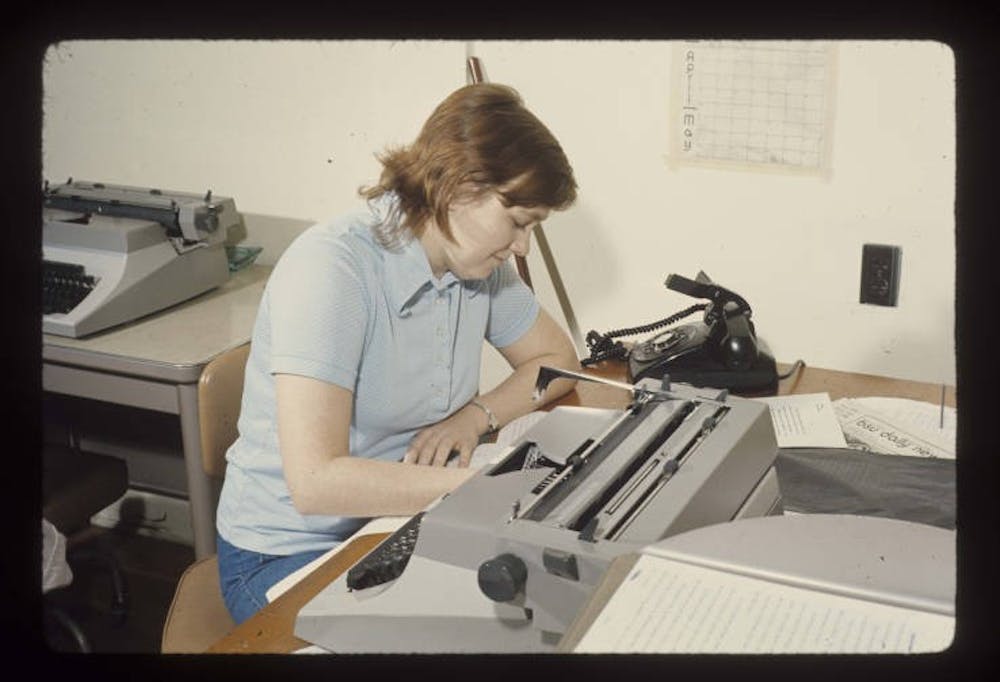

The house on North College Avenue no longer exists, iMacs have replaced typewriters, and breaking news notifications have replaced the Associated Press teletype machine. This desire for evolution, in a way, has been a major part of the news industry the last 100 years, Key said.

“The industry is changing and evolving to reach readers,” Key said, “and we’re evolving and changing to figure out the best way to monetize our news content. So it’s a very interesting time in journalism.”

Contact Joey Sills with comments at joey.sills@bsu.edu or on Twitter @sillsjoey.