Content warning: This story contains descriptions and images related to a school shooting that may be triggering to some readers.

Joey Sills is a freshman journalism news major and writes “Talking Head” for The Daily News. His views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

The first time I told anybody in my extended family that I was considering studying journalism in college was at a Cheddar’s Scratch Kitchen in Terre Haute, Indiana.

I was there with my dad, my step-mom, my two younger sisters and my grandmother and step-grandfather, who were visiting before I would visit my dad’s for the last time before I left for school, a month or so before I started at Ball State.

My grandparents had asked me what I intended to major in, and I told them I was interested in studying journalism and political science. This information was met not with encouragement but with an extended rant from my step-grandfather on the dishonesty of the media and its perceived unwillingness to cover anything besides the pandemic or the previous president.

This only continued a pattern of media mistrust that the previous president stoked. Former President Donald Trump infamously called journalists “the enemy of the American people” on Twitter Feb. 17, 2017. In 2020, he called the image of police brutality against a reporter “a beautiful sight,” and the branch of my family who derided my career choice very much supported him.

This event didn’t bother me, per se — I didn’t need anybody to validate my chosen profession or tell me I was doing a good job. But it stuck with me, nonetheless.

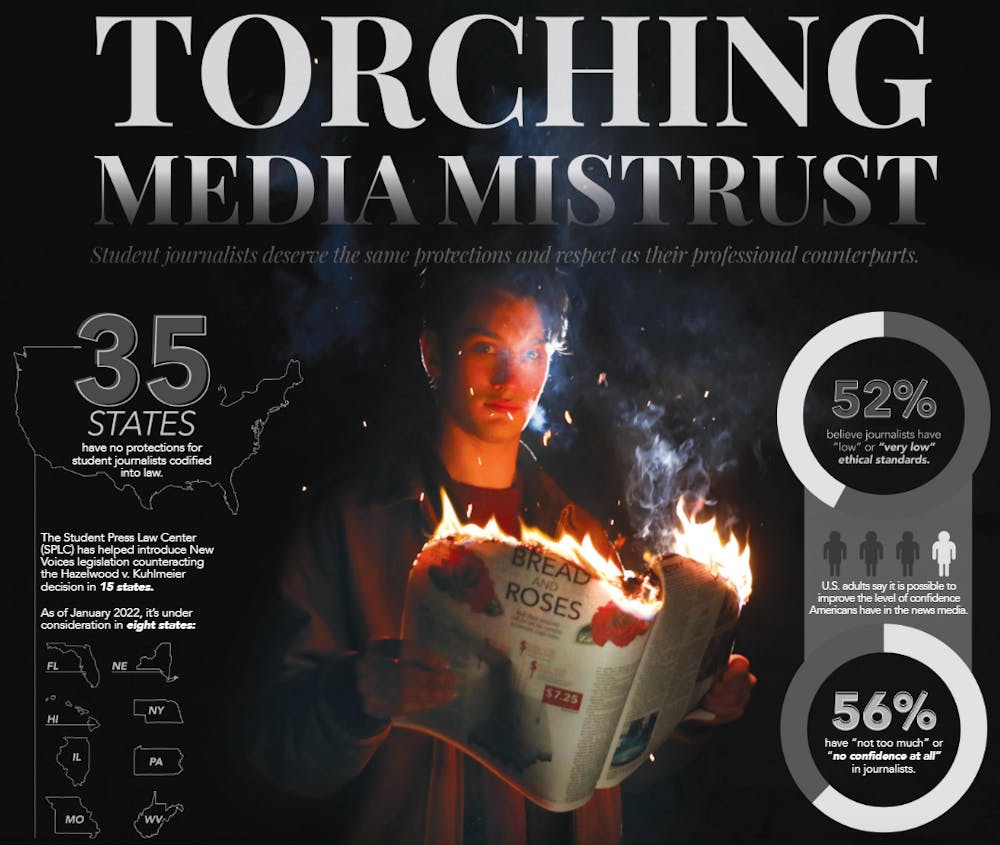

It turns out this isn’t such an uncommon occurrence. According to a 2020 Pew Research Center poll, 52 percent of Americans have “not too much” or “no confidence at all” in journalists while 56 percent believe journalists have “low” or “very low” ethical standards.

The prospects become even more grim for student journalists. In 1969, the Supreme Court decided in the case Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District that students don’t lose their First Amendment rights “at the schoolhouse gate.”

But, nearly 20 years later, in 1988, the Supreme Court in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier argued nearly the exact opposite. In a case involving a principal at Hazelwood East High School in St. Louis blocking certain pages of The Spectrum, the school’s student newspaper, from being published, the court ruled in favor of the school district. The court argued schools could exercise such prior restraint as long as the action was “reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns.”

The court never specifically outlined what those “pedagogical concerns” could be, leaving the discretion for such a decision entirely to the administrators who practice the restraint.

This effectively means, by law, student journalists don’t have the same rights under the First Amendment as professional journalists. In an effort to remedy the Hazelwood decision, the Student Press Law Center (SPLC) has helped champion a student-led effort to introduce laws protecting student journalists called New Voices — but, even so, only 15 states have adopted such legislation.

What about our work makes it less important than that of our professional counterparts? Why are we denied the same basic rights they are given? As a student who’s only been reporting for about six months now, I ask myself these questions often — they’re even more baffling to those who have dedicated much more of their lives to storytelling.

To recognize Student Press Freedom Day 2021, SPLC released a report titled “Student Journalists in 2020: Journalism Against the Odds,” which detailed not only the importance of student journalism but also the censorship that occurred at the hands of schools.

For example, in Oklahoma, an anonymous high school student reported they were instructed not to publish an article about teachers resigning due to the safety concerns invoked by the COVID-19 pandemic.

James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, similarly blocked release of data by The Breeze, the university’s student newspaper, regarding on-campus versus off-campus infection rates.

The distribution of a high school yearbook in Texas was temporarily blocked by the superintendent because images depicting the Black Lives Matter movement “would not sit well” with the predominantly conservative community.

In total, 69 student journalists from 24 states responded to SPLC’s request for examples of censorship — the three I just described are but a fraction of the problem student journalists face on a daily basis. I cannot claim I’ve ever been a victim of academic censorship, but I can empathize with those who have. A systemic problem that affects even one student journalist affects us all.

Being a journalist can be a tough job requiring a tough individual. I’m entering a field in which the public I’m hoping to serve might hate me simply for being in that field. However, can I prepare myself for a rigorous career if there’s a possibility the publication I use to expand my resume can be censored by the very institution that claims to value academic freedom?

By the very nature of our status as student journalists, our work is harder to defend in a court of law — some courts would say the First Amendment doesn’t apply to us, purely because of the adjective before our title.

The examples of student journalists working against the odds and producing a breaking story are numerous, but I believe among the most poignant is that of the reporters at The Eagle Eye, the student newspaper at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

On Valentine’s Day 2018, Marjory Stoneman Douglas was the location of the deadliest school shooting in United States history, with 17 people killed and another 17 injured. The shooting — which, according to the Associated Press, lasted six minutes and 20 seconds — was no doubt one of the most terrifying, if not the most terrifying, moment of these students’ lives.

However, realizing the reality and importance of the situation, the student reporters at The Eagle Eye began reporting the story even as the undeniable echo of gunshots rang down their hallways.

According to the Columbia Journalism Review, several writers for the newspaper crammed into a closet adjacent to their journalism classroom to hide. At the time, they weren’t certain whether this event was a false alarm, a drill or the real deal — regardless, they knew it was newsworthy. It’s because of this sense of urgency that we have primary accounts like senior student Ryan Deitsch’s videos of students being hidden in classrooms and senior David Hogg’s videos interviewing students as the tragedy unfolded.

Although The Eagle Eye did not receive a Pulitzer Prize in either public service or breaking news reporting, it was specially acknowledged at the 2019 Pulitzer Prize announcement.

“These budding journalists remind us of the media’s unwavering commitment to bearing witness — even in the most wrenching of circumstances — in service to a nation whose very existence depends on a free and dedicated press,” Pulitzer Prize administrator Dana Canedy said. “There is hope in their example, even as security threats to journalists are greater than ever.”

These reporters demonstrated not only the power of student journalism but the power of impactful journalism — period.

It would’ve been easy for the student reporters at The Eagle Eye to forgo an issue entirely to process the event that occurred. It would’ve been easy for Marjory Stoneman Douglas to halt publication of the paper for the week following the shooting. It would’ve been easy, and perfectly legal, for the school to review the issue prior to publication.

But they published the paper. It was published as is, and it was all the better for it.

That night at Cheddar’s, I agreed with what my step-grandfather was saying because I wanted to keep the peace. It was easier to pretend I felt the same way than it was to argue an opposing point. I like to think I’ve moved beyond that, though, even if he hasn’t.

This is a world that is skeptical of journalists, both student and professional. We sometimes present a truth others don’t want to hear, and we’ve been punished for it. But, regardless of what the government or my step-grandfather says, I’m proud of what I’m studying, and I always have been.

It’s time I make that clear to everyone who asks.

Contact Joey Sills with comments at joey.sills@bsu.edu or on Twitter @sillsjoey.