KwaTashea Marfo is a freshman public relations major and writes “Imperfectly Perfect” for The Daily News. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

From kindergarten to eighth grade, I attended Gary Community Schools. Transferring to Portage High School after eight years at a predominately Black school was a culture shock. It sank in my sophomore year as I sat in my dual credit U.S. History class filled with my peers — all white but for four students — and laughter roared in my ears. My teacher asked me to read a complex word, casting me as a victim of the impossible literacy test typically given to enforce a barrier on African Americans to prevent them from voting during the Jim Crow era.

Still, typically anxious, young Tash couldn’t say the word correctly.

As I suddenly felt empathetic to the predecessors I had never known, I felt uncomfortable in my skin. As tears ran down my face, I knew my education's structure wasn’t right.

It hadn't always been this way for me. Looking back to my time in Gary, Indiana, during my first eight years in the educational system, every February was spent learning about different African American leaders who helped shape the United States. From the enslaved people first brought over from Africa during the 17th century to Black icons in the modern day, I looked forward to the month of February every year because it was my chance to focus deeper on these influential individuals and celebrate their achievements with my teachers and classmates.

In class each day, we would pick an individual to study and analyze their role in creating U.S. history. By the end of February, students were required to complete a project in which we wrote research papers and created interactive posters that covered the timeline of a selected pioneer and the ways they contributed to the Black community or society as a whole, complete with quotes and a memorable lesson. My favorite part was when I could wear my traditional African garments, which I did faithfully for eight consecutive years.

The fabrics were rich in color with bright textiles and patterns that often reflected the Ashanti tribe in Ghana, West Africa — where my father is from. Something about wearing the Ankara garments while reciting information about these individuals allowed me to take pride in my cultural history.

I felt seen. I felt heard. I felt proud to be a young African American woman!

This feeling vanished when I transferred to Portage High School in Portage, Indiana, my freshman year. I soon realized the devotion I had to learning about my cultural history was thanks to Gary Community Schools, an education system that catered its curriculum toward the targeted demographic of its population.

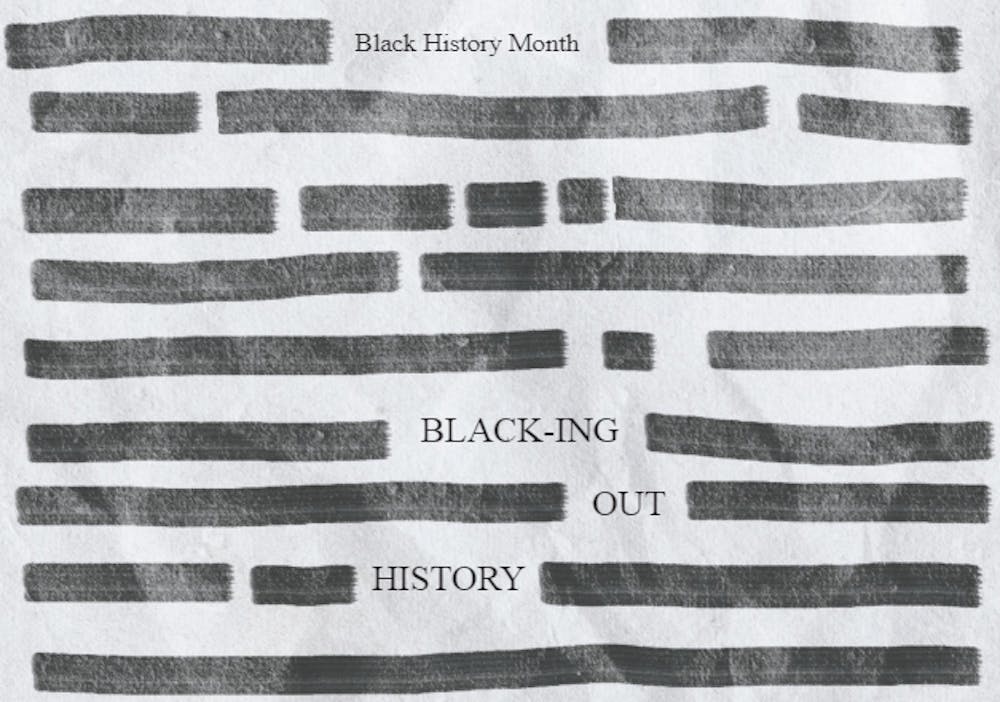

While attending Portage High School, I noticed a pattern in the lessons being taught: much of African American history was missing from the curriculum. Many Black figures hidden from history deserve a long-overdue spotlight to celebrate their contributions to civil rights, politics, arts and more, even outside of a month that has 29 days in a good year.

The curriculum at Portage High School should have been structured to teach African American history in culturally responsive ways year-round. Specifically, white teachers whose only objective was to share the accomplishments of prominent figures such as Rosa Parks, Fedrick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr. should not have ignored the impactful history of unsung heroes like W.E.B. Du Bois — a sociologist, socialist, historian, civil rights activist, among other things, who led the Niagara Movement and later helped form the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

It’s imperative that predominantly white school systems find a way to connect with all of their students on more than an academic level — but an emotional level as well. Far too often, students are presented with a version of history that centers on the accomplishments of our country’s white forebears.

When confronted with a history that does not deify the actions of white America, students are not given respective resources for interacting with said history. Some prominent examples of this are the painful truths behind the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre that resulted in a Black neighborhood perishing at the hands of a violent white mob or understanding the significance of the federal holiday Juneteenth, intended to commemorate the emancipation of enslaved people in the U.S.

When our curriculum centers its lessons on a sanitized version of history, students are not taught how to respect and appreciate cultures different from their own, resulting in insensitivity and distrust toward people of color. Sadly, that type of sanitized history is being made into law — as we speak — in the Indiana State Senate.

Under House Bill 1134, conservative lawmakers are currently constructing a series of proposals that would restrict “harmful materials” concerning the teaching of divisive concepts like of an individual’s sex, race, religion, political affliction, among other things, in the classroom. Furthermore, the bill also provides parents with a voice to determine whether they want their students to opt-in or opt-out of specific educational activities.

From the perspective of an African American woman, this bill is absurd. It should not be controversial. Our schools’ curriculum on race is already censored — with this bill, lawmakers practically rewrite history and discourage people from thinking independently and critically.

Even if this bill passes, the fact will remain that America has a long complicated history with race.

Stopping students from receiving an inclusive, equitable education will not shelter them from news concerning racial discrepancies in the world but rather a delayed response to such events. With bills such as HB1134, the minds of the youth will deteriorate into a cultural and intellectual decline.

Our students’ already little knowledge about well-known African Americans, such as Jackie Robinson or Harriet Tubman, will be erased. You can forget learning about George Washington Carver, an agricultural scientist and inventor who promoted crop rotation to prevent soil depletion and created 300 uses from peanuts and 118 from sweet potatoes. You can forget learning about Ida B. Wells, an American investigative journalist, educator, early leader in the Civil Rights Movement and a founder of the NAACP.

Teaching lessons about a critical race theory denotes that systemic racism is part of American society and recognizes that racism stems from more than an individual's bias and prejudice through embedment of laws, policies and institutions such as education, employment or healthcare. Discussing this philosophy is important because it accurately depicts American history, the good and the bad, no matter how gruesome it may get. If we are willing to censor students’ topics, how will they become the future politicians, doctors or teachers of America? Where will they get their resources to progress into a better society that promotes divisive concepts?

America will no longer be worthy of being known as a melting pot and will crumble as its people struggle to coexist and live together as a nation, because the unbearable weight of holding together a society of entangled cultures with little understanding of one another is inevitably going to collapse atop us all. When this happens, lawmakers will learn discussing topics that evoke discomfort is beneficial.

It’s agonizing even to imagine the drastic difference my educational experience in Gary Community Schools would have been if this bill was in effect when young Tash was learning about her favorite unsung heros. The sole purpose of discussing diverse history topics is to reflect, observe and understand complex dilemmas by examining how the past has shaped our society and its people. Even with politicized issues such as critical race theory, the goal is to teach the true magnitude of the intersection of race and law in the U.S. and how it challenges American approaches to racial justice.

During my high school career, eight years of critical race theory knowledge was challenged by naïvete, discrimination and taboo topics about the cruel history of my predecessors. With education systems following our country's systemic racism blindly and HB1134 threatening to erase hundreds of years of history, young Black students will wonder why they won’t get the chance to engage with their cultural history, and as a result, lose the self-esteem and empowerment Black knowledge gives.

From where I am standing, discussing these topics in a school environment where information is given, resulting in acquired knowledge on various fields of education, promotes character/mindset development and social cohesion.

After all, I was in a school setting when I learned about Ruby Bridges — a civil rights activist who was the first African American child to desegregate William Frantz Elementary School during the New Orleans school desegregation crisis on Nov. 14, 1960 — who inspired me to ignore the roaring laughter and prove the naysayers wrong.

Contact KwaTashea Marfo with comments at kwatashea.marfo@bsu.edu or on Twitter @mkwatashea.