As a director whose cult following has grown enormously over his career, Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch was not to be anticipated lightly. Originally set to premiere in July of 2020, Anderson’s fans have been eagerly waiting after his last major live-action film, The Grand Budapest Hotel premiered in 2014.

This picture takes a step beyond Anderson’s past works, and while abandoning some of his signature storytelling techniques, he still managed to successfully create a piece of art that is fresh and unique while maintaining that signature Wes Anderson style.

“A love letter to Journalists”

The French Dispatch follows the creation of a Kansas newspaper’s final edition at their foreign bureau in Ennui-sur-Blasé, France. In his will, editor Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray), expresses that, upon his death, the newspaper should produce one last issue before permanently ceasing production. So, when he suddenly dies of a heart attack, the paper’s journalists scramble to choose three main stories published over The French Dispatch’s lifetime to include in their final “farewell” issue.

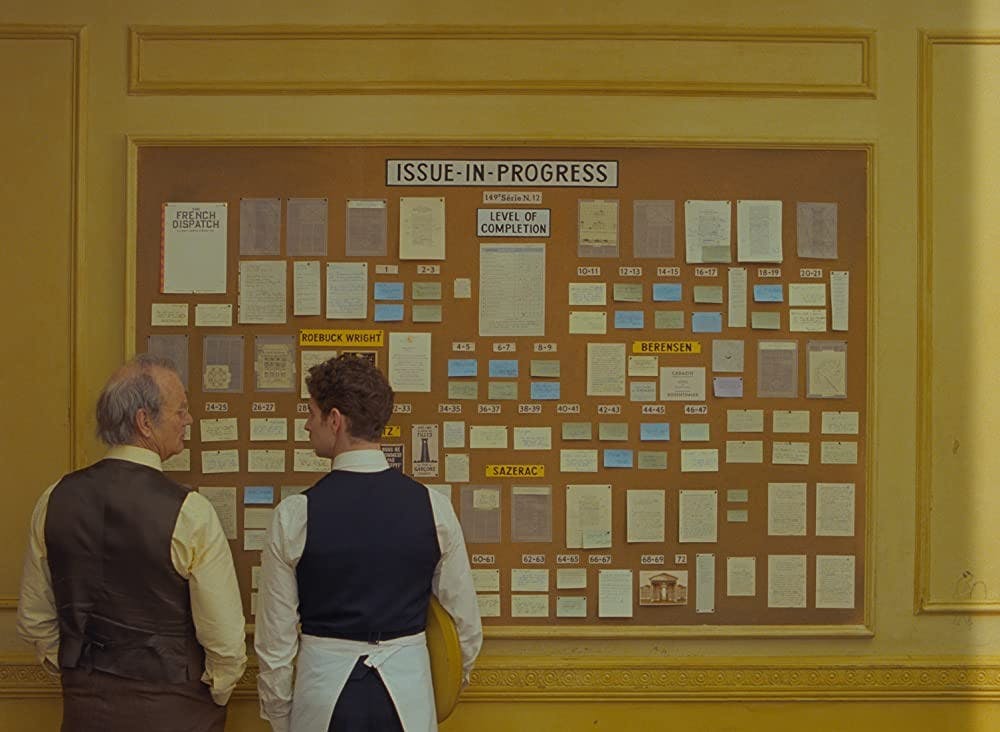

The movie is set up to be viewed as a newspaper is to be read, in sections. The very first section establishes pertinent information the audience should know for the remainder of the film. Even though this establishment of plot is interesting, it doesn’t save the audience from genuine confusion; I often found myself thinking, “Do I lack the intelligence for Wes Anderson?” And also, “Do I understand English?” I do, as I would soon rediscover, but the quick-witted, fast-paced narration felt like it was not setting the scene and instead setting me up for failure.

Image from IMDB

The bulk of the film, told in one short story and three full pieces, eased my mind. They were captivating and (mostly) easy to follow. The short story by “cycling-journalist,” Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) highlights and compares parts of Ennui in its past and present states. The first full story follows artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro) who’s in prison/asylum for murder. When the nude abstract portrait of his guard and ultimate lover is bought by Julien Cadazio (Adrien Brody), Rosenthaler becomes an art-world legend. The next section follows the wildly eccentric French student protest-turned-chess-match, led by Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet), and reported on by Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand). The final story follows journalist Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) as he recounts a meeting with the Commissaire of the Ennui police force that goes amiss when the Commissaire’s son gets kidnapped. In the end, the employees of the French Dispatch write the obituary for Howitzer, together. It leaves the film on a somber, but content note. With so much of their hearts being exposed in the process, it’s no wonder The French Dispatch is billed as a “love letter to journalists.”

All of these stories bring very unique elements to the table. Where the “cycling-journalist” piece mainly uses witty anecdotes and beautiful tableaus to successfully tell its story, Roebuck Wright artfully dictates the foods and tastes he encountered on his adventure with supporting cartoons and intricate visuals. Futile conflict and lethargic characters, though consistent throughout the entire film and an Anderson staple, really shine through in the first story about the artist. Every little piece of The French Dispatch came together to create a really beautiful film.

Creating a new world with (not too much) reckless abandon

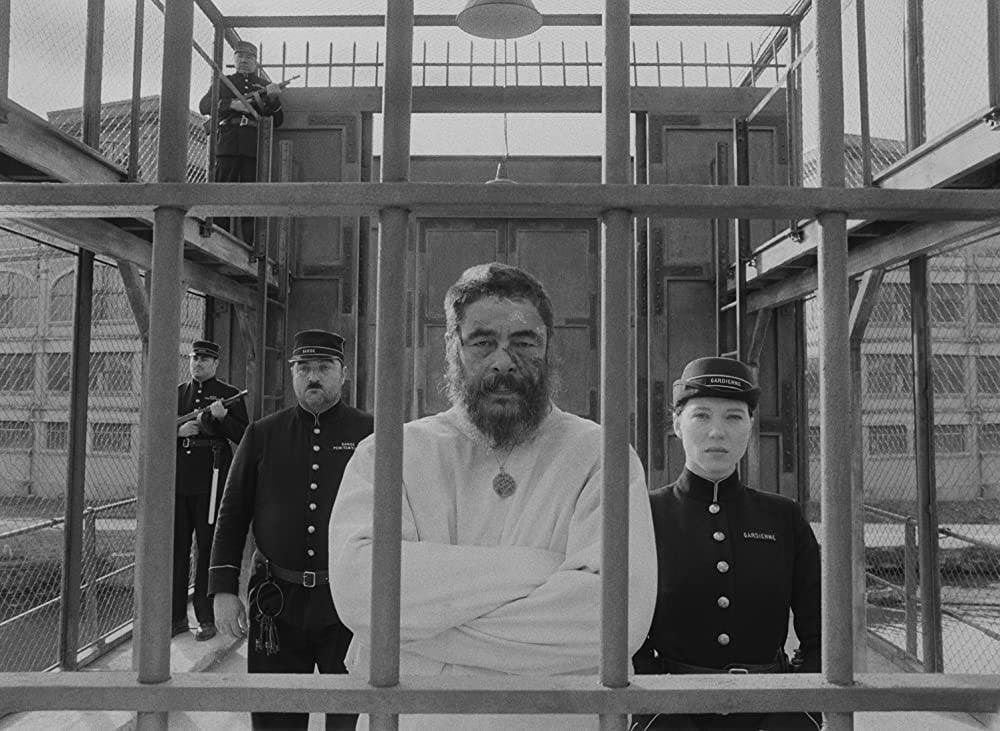

Anderson’s use of color is so prevalent in his movies that fans and artists alike have dedicated themselves to its analysis. Anothermag.com published a great homage to his palettes and included this quote from Hamish Robertson, an artist and Wes Anderson fan, who said, “Anderson’s colour palettes are integral to his cinematic ‘world-building’...They ultimately become their own visual language...allowing an immersive visual experience whether the sound is on or not.” So when I realized The French Dispatch was almost entirely in black and white, I was surprised to say the least. Anderson seemingly abandoned the colorful world in which he has spent his entire career building.

Of course, color wasn’t fully thrown out the window. In fact, it came into play during very particular, important moments. For example, in the first story of the series, the imprisoned artist is painting a portrait of a nude woman. The entire scene is in black and white until his final piece of art is revealed. Then the entire room comes to life and the abstract art he created is shown with a full, vivid pigment. This is the piece that goes on to make the artist incredibly famous later in the story.

Image from IMDB

When the scene is set in the office of the French Dispatch itself, it’s always in color. And, in perhaps my favorite part of the movie-watching experience, there’s an entire scene in black and white and, for only a few seconds, Saoirse Ronan peeks through the slot in the door and her huge, beautiful, blue eyes are illuminated in color; a single “wow” echoed through the audience.

Anderson earned his use of color. He tested the resilience of his work with The French Dispatch by withholding color, and it works. By forcing the audience to savor color when we were only allowed a small glimpse, his famous palette was even more transcendent.

Put this thing on the stage

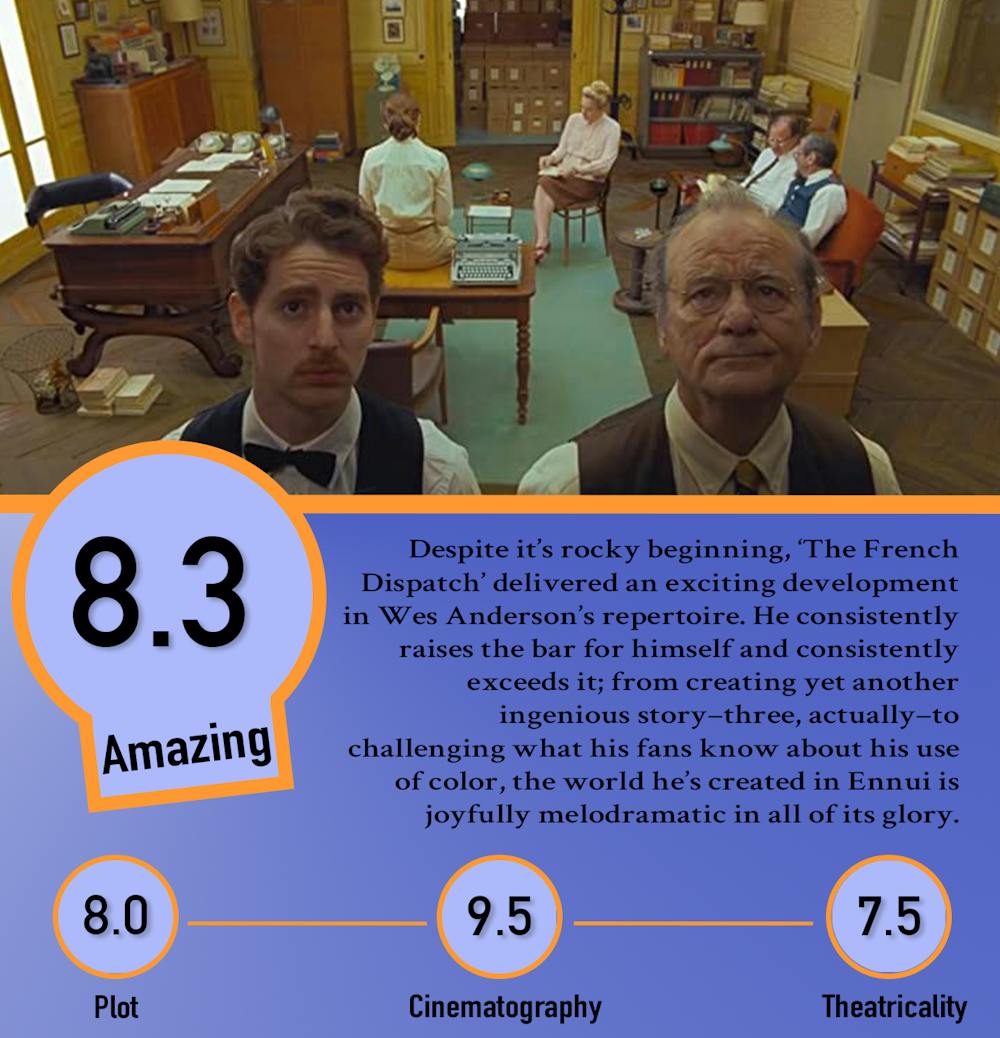

Anderson’s use of framing, melodrama, and design elements mold together to create a pleasantly theatrical piece, and part of that is thanks to his use of framing.

Image from IMDB

His shots are balanced in strategic tableaus. When it’s time for a character to say something important, or gain more attention, the actor moves to “downstage.” In theater, “downstage” is the closest part of the stage to the audience. So, while a camera can move itself to emphasize an actor, Anderson allows the scene to be set in place for the actor to move within the frame in a more purposeful way. He utilizes spotlights to emphasize the subject even further.

The unique characters in this film are fully realized, beautifully performed, and expertly placed in Anderson’s stylized world. Every small movement is perfectly calculated and purposeful, a detail that makes Anderson’s work so entertaining. This style includes nearly lifeless eyes and a very blasé attitude confined in exceptionally ridiculous storylines, but sometimes these elements can make Anderson’s movies seem silly and overdramatic. However, it’s all on purpose, and that’s what makes his work so fun. The comedic timing of his actors and his writing is so on point that it gives profundity to an otherwise “silly” film.

Images: IMDB

Featured Image: IMDB

Sources: NME, Another Mag