Joey Sills is a freshman journalism news major and writes “Talking Head” for The Daily News. His views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

In the shadow of Texas’ recent anti-abortion legislation and the Supreme Court’s failure to block it, the calls for court reform have once again entered the political conversation.

We first heard debates on the topic soon after the death of former Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Sept. 18, 2020, and those debates amplified following the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett just eight days before the 2020 presidential election.

A year later, we’re seeing a similar problem with Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer’s stubborn refusal to retire even while the Democrats hold onto the White House and the Senate. Ginsburg expressed the same sentiments in 2014 when she refused to retire just months before the midterm elections handed control of Congress to the Republican Party.

To the progressives already calling for court reform, Breyer’s line of thinking is a bit too close to Ginsburg’s for comfort.

One way reformists suggest addressing the possibility of a 7-2 conservative majority on the court is to simply expand the court to as many as 13 justices. Progressive congressmen like Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., frame this demand as a way of balancing an increasingly partisan body by matching the number of justices with the number of U.S. courts of appeals. Conservatives like Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and moderate liberals like Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., however, argue this move is nothing more than a progressive power-grab, vowing to block any attempts Democrats make at “packing the court” with justices who will rule in their favor.

The problem with expanding the court is not that it’s necessarily unconstitutional or the wrong thing to do. Article III of the Constitution leaves the makeup of the court to Congress, and the number of justices in its ranks has ranged from as little as six in 1789 to as many as 10 in 1863.

The problem with expanding the court is that such reform doesn’t go far enough.

How is having 13 unelected, life-serving judges determine the constitutionality of popular legislation any more democratic than having nine unelected, life-serving judges do the same thing?

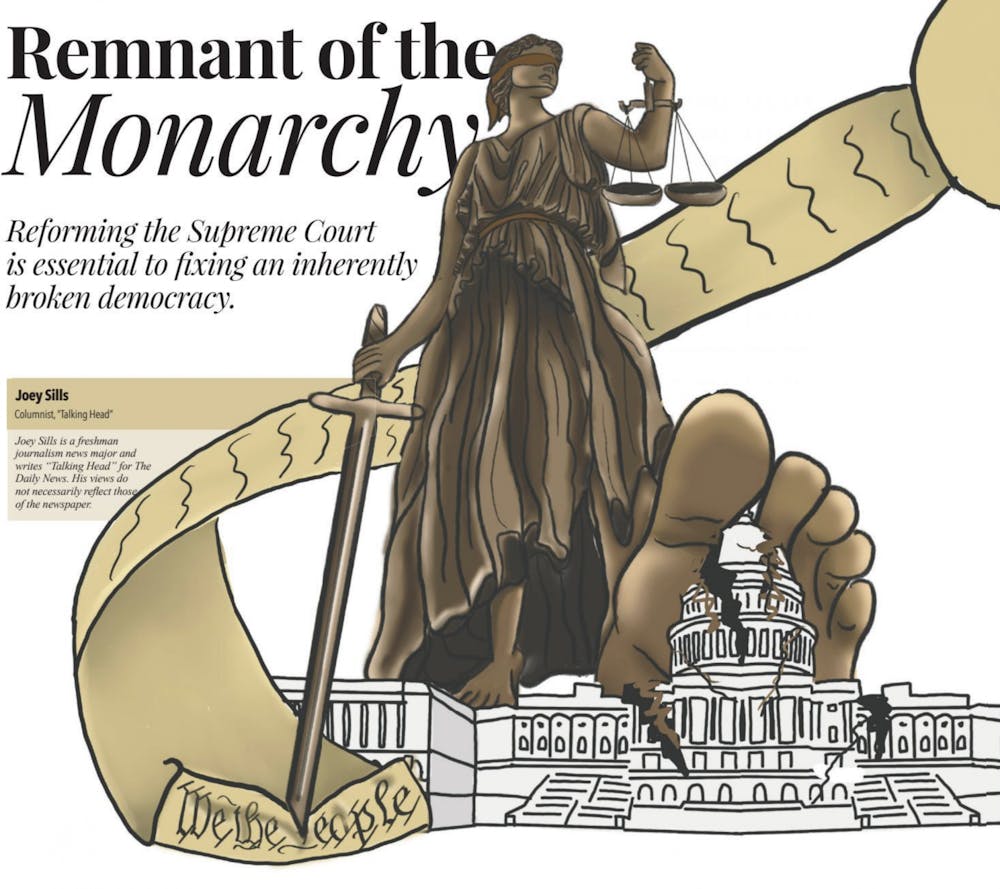

A system that gives so much power to a handful of individuals does not seem to be one that takes into account the popular consensus. I would even go so far as to argue it’s the closest thing in our society to a remnant of the monarchy.

Supreme Court justices are first chosen by the president, who himself is elected by the Electoral College, a system that forgoes the popular vote in favor of a “winner-takes-all” rationale, in which the winner of each state gets all that state’s votes regardless of how many votes their opponent received. According to a report from Gallup, 61 percent of Americans support abolishing the Electoral College in favor of a popular vote system. Pew Research Center reported a fairly similar majority, with 55 percent of those surveyed preferring a popular vote system.

They are then confirmed by the Senate, a body that, by design, overrepresents smaller states with less population. If you add together the populations of the three most populated states — California, Texas and Florida — you’ll see those states’ six senators represent roughly the same number of people as the 64 senators from the 32 smallest states.

And, should the justice be confirmed by the Senate, they retain their new position for life, unless they’re removed from office — a process that has only been attempted once, to no result, with the impeachment trial of Justice Samuel Chase in 1805.

These justices have a lot of power — more power than the Constitution ever explicitly gave them. Judicial review, the ability of the Supreme Court to review executive and legislative action to determine its constitutionality, is not once mentioned in any of our founding documents.

Yet, it’s become the primary function of the court since former Chief Justice John Marshall granted himself and his colleagues this power in the 1803 landmark case, Marbury v. Madison.

Years later in 1820, former President Thomas Jefferson famously said, “To consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions [is] a very dangerous doctrine indeed and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.”

Oh, if only he could see the state of the court today.

This isn’t to say the concept of judicial review is entirely unnecessary or illogical — it’s important Congress is held in check. It’s even proven, on occasion, a decent strategy in practice.

Landmark cases like Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, and Roe v. Wade, which cemented a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion, both took a progressive view of the Constitution that has affected us to this day.

However, for every one of these decisions, there’s a Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission, which allowed for unlimited corporate funding of campaigns, or Shelby County v. Holder, which effectively gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by determining preclearance of election laws in historically discriminatory states unconstitutional.

You can’t convince me the majority of Americans would’ve supported corporate influence in elections or restrictions on their fundamental right to vote.

This is why the most sensible course of action is to pair short-term, structural reforms like expanding the court and imposing term lengths with a strike at the heart of the Supreme Court’s power by weakening judicial review.

Yes, the court must be ideologically balanced and expanded to represent the changing American population. Yes, it is reprehensible that Supreme Court justices are the only officeholders in the federal government to not be subject to term lengths. But we can’t simply achieve these victories and call it a day when the ultimate problem of the court lies in its power to render any legislation it so wishes null and void.

The court itself is fundamentally broken, and we must treat it as such.

To prioritize the will of the people over the will of the court, all cases of judicial review should be decided on a 7-2 — or 9-4, should the court be expanded — supermajority.

This ensures that if the minority party only holds a simple majority on the court, the decision-making authority on all but the most egregiously unconstitutional legislation would be left to the more democratic branches of government. It would also require the majority faction to put more time into compromising with their colleagues across the aisle, theoretically leading to less disastrous decisions going forward.

It would be naive to believe these reforms alone would solve every problem with our democratic process. Abolishing the filibuster, making it easier to vote, giving Washington, D.C. statehood, publicly financing elections and many other solutions are requirements for establishing a truly popular democracy.

But what good are these solutions if we’re burdened by an increasingly partisan and undemocratic Supreme Court that can strike down this sort of legislation at will?

Reforming and weakening the court may not entirely fix our broken democracy, but it certainly isn’t a bad place to start.

Contact Joey Sills with comments at joey.sills@bsu.edu or on Twitter @sillsjoey.