John Lynch is a senior journalism news major and writes “Fine Print” for The Daily News. His views do not necessarily reflect those of the newspaper.

Growing up, “Star Trek” always had a hold on me.

Gene Roddenberry’s groundbreaking series, which has now spawned a dozen-odd shows over six decades, always envisioned a world where our differences were relics of our past. Captain Kirk and the crew showed us a world where humanity’s goals were no longer based on our desire to dominate each other but rather to explore the stars and work for the common good.

I don’t think Elon Musk got the memo.

The problem I always had with “Star Trek” was it was set in the future, meaning I wouldn't get to see that idealistic utopia come to be. People like Musk, owner of automotive company Tesla and space travel company SpaceX, are actively making that disappointment worse.

Our motivations to go to space, simply put, are not pure. That’s not to suggest they ever were — the whole reason the space race of the 20th century happened was to put nuclear weapons in space to get the upper hand in the Cold War — but our motivations for leaving our blue marble behind haven’t exactly gotten any better.

Billionaires like Musk, Jeff Bezos or Richard Branson, who have all invested heavily in space exploration and transportation, aren’t in it for the final frontier — they’re in it for more money.

To understand how we got here, we need to look back through several decades of space travel. Following the success of the Apollo missions to the moon, continuing the space race became too expensive and politically unpopular to continue receiving the plentiful funding it had enjoyed during the ‘60s, according to a National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) report.

NASA would continue on after the moon landing with the launch of the Space Shuttles, reusable exploration vehicles that would eventually be responsible for the deployment of hundreds of vital satellites like the Hubble Telescope and the International Space Station (ISS). However, even with the success of the ISS, sending astronauts to space became cost prohibitive, and NASA’s funding stagnated.

Just as importantly, NASA’s work has given the world countless scientific advances that we use in our day-to-day lives. We owe CAT scans, LED lights, modern home insulation, baby formula, phone cameras and, most importantly, portable computers to the innovations NASA made during their space race heyday. How many of those inventions do you think for-profit companies would have given the world out of the kindness of their hearts?

At its peak in 1964, NASA’s budget was more than $57 billion, or more than $500 billion in today’s money, a truly massive sum at the time. NASA’s budget for 2021? $24.8 billion.

Enter the billionaire astronaut. In the early 2000s, as the Space Shuttle program began to wind down, private companies began to see success in the world of space travel. Notable players like Musk’s SpaceX, Branson’s Virgin Galactic and Bezos’ Blue Origin have all now sent multiple successful flights into space. These missions accomplished a variety of tasks in their early years, including test flights, satellite deployments and supply runs to the ISS.

However, it comes with a big caveat: These guys are privatizing the final frontier.

To call these ventures vanity projects may, in fact, be inaccurate — silly even. But what exactly were we aspiring to when Musk shot a Tesla Roadster into orbit in 2018?

The starship “Enterprise,” it was not.

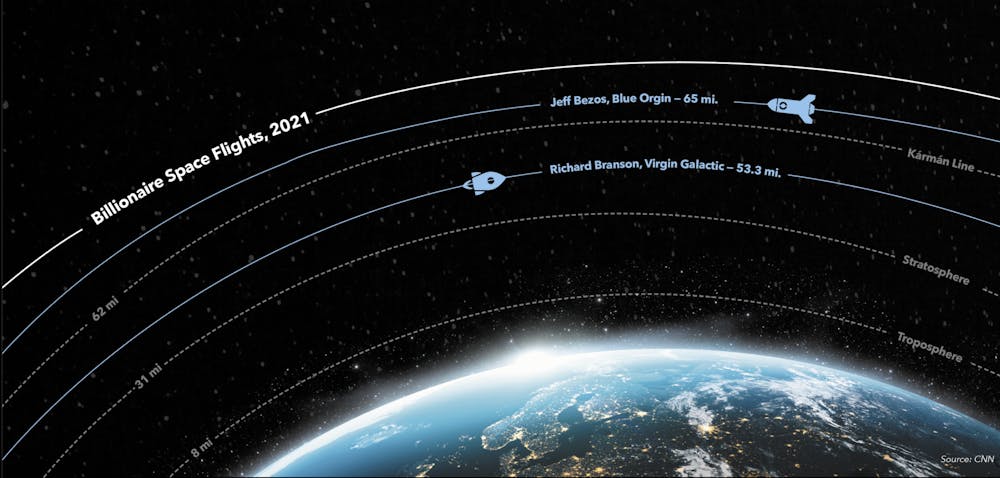

2021 has been the year of the billionaire astronaut, a space race in its own right fueled by the egos of some of the most fantastically wealthy people in the world. Branson made it to space on July 11 while Bezos had to languish in terrestrial gravity until July 20. Poor guy.

Maggie Getzin, DN Illustration

As it turns out, billionaires are not, in fact, explorers. They’re businessmen first and foremost, and they will continue to be businessmen no matter where in our solar system they are.

The funny thing is, Musk, Bezos and Branson may genuinely believe they are helping the world by pushing the privatization of space into the modern age. They might even be right. However, they’re not doing it for the right reasons.

We are not going to space anymore to further human knowledge or unlock the secrets of our universe. We’re going based on ego and profit.

Yes, SpaceX intends to put humans on Mars.

Yes, private companies have picked up the slack where NASA was unable to continue in the 21st century.

No, that doesn’t make them right.

The idea of space exploration has captured the imagination of millions of people and brought even more together. The moon landing — which is real by the way — united the country when they watched Neil Armstrong take his “giant leap for mankind.” Millions of people around the earth were able to live through history as we pushed toward a goal few thought we could achieve.

The difference between these eras of space travel comes from who owns the means of getting to space.

Keep in mind, some of these space venture capitalists have only gotten as far as they have with substantial help from the U.S. government. As of 2015, Musk's ventures like Tesla, SolarCity and SpaceX have received $4.9 billion dollars in government funding. While the private sector has been successful in space, they wouldn’t be there without a lot of help from taxpayers. If we’re willing to fork over that much money to the private sector, which we have no control over, then why not fund our own program?

We’re already about to witness the beginning of space’s transition to the public sector. NASA intends to put astronauts on the Moon via its new Artemis program in 2024, but guess who’s going to be taking us there? SpaceX and its $2.89 billion contract with the agency.

With NASA at the helm, space travel and exploration were the property of the government and, to a certain extent, the people. With the Musks and Bezos of the world leading the charge, the knowledge we could gain and the progress we could make are in the hands of for-profit corporations.

The precedent is too dangerous, and there is too much at stake to put our future in space in the hands of the rich. Our intentions have never been perfect in space, but that doesn’t mean we can’t take our next “giant leap” with better ones.

Contact John Lynch with comments at jplynch@bsu.edu or on Twitter @WritesLynch.