Not a Normal Morning

Tom Gubbins woke up earlier than usual that Tuesday morning. It was before 9 a.m., and his radio was on and set to his typical station, one that would normally play “The Bob & Tom Show.” But, instead of the satirical humor he was used to listening to while getting ready, Gubbins heard announcements from CNN Radio, a station he didn’t know existed.

At first, he thought it was a new skit of Bob and Tom’s, but, after listening with closer attention, Gubbins realized something was off.

He quickly turned on his television, and, on every channel, he saw the twin towers — one standing as normal, the other billowing with smoke. The first plane had just hit the World Trade Center. It was Sept. 11, 2001.

“I remember jumping into the shower, brushing my teeth with one hand and shaving with the other,” said Gubbins, 2002 Ball State alumnus and editor-in-chief of The Ball State Daily News for the 2001-02 academic year. “I couldn’t get to the newsroom fast enough.”

The second plane hit as Gubbins left the old Phi Delta Theta house for the Art and Journalism building, running his normal route through the Quad to get to the newsroom.

“That walk — it was so surreal,” Gubbins said. “There was not a cloud in the sky. Obviously, there wasn’t a plane in the sky. It felt weird. Nothing was moving.”

Gubbins was one of the first people in the newsroom that morning, as many people still didn’t know what was going on halfway across the country in New York. When Gubbins walked in, Marilyn Weaver, Ball State professor emerita, looked him in the eyes and said, “This is your classroom today. Get your staff in here — nobody goes to class.”

“The newsroom is your classroom”

Gail Werner, Ball State executive writer and 2004 alumna, was one of the chief reporters of The Daily News staff that year. After getting ready for her history class that morning, Werner walked past a group of students gathered in front of the television in Botsford-Swinford Residence Hall.

“I remember asking myself, ‘Oh, I wonder what they're watching,’" Werner said, “but I didn’t think anything of it.”

Werner boarded the shuttle bus she took to history class Tuesday mornings, one typically crowded with students chatting. That morning, Werner said, the bus was so quiet “you could hear a pin drop.”

“They had the news on,” Werner said, “and we were all just hearing them say a plane had hit the towers … I charged to [the Art and Journalism building] to see what was going on.”

Werner arrived to see her graphics class standing outside the newsroom, with her professor, Jennifer Palilonis, George and Frances Ball Distinguished Professor of Multimedia Journalism, explaining to her students, “there’s no place more important you need to be today than in the newsroom.”

Emmet Smith, 2003 Ball State alumnus and creative director of The Daily News during the 2001-02 academic year, woke up to a phone call from the newsroom that morning and the twin towers burning on his television. After being asked if he knew what was happening, Smith said, only one other question was asked before hanging up the phone.

“Jenn [Palilonis] wants to know, 'why the hell you aren’t in here yet?'”

Palilonis had just started as a professor at Ball State three weeks earlier, after leaving the Chicago Sun-Times as the news design director. When she first heard the news, she said, it was hard for her to accept that she couldn’t be back in the newsroom.

“It didn’t feel right to be teaching in Muncie, Indiana,” Palilonis said. “I felt that itch that you have as a journalist to be in a newsroom covering this incredibly massive, horrifying news event. It was a weird feeling to not be there.”

After taking time to process what she was watching live on the news, Palilonis said, the shocked and stunned feelings left as she “immediately” realized she had to get to work — not to teach her classes, but to help the students of The Daily News.

“At that moment in time, [being in the newsroom] was the only thing I knew to do,” Palilonis said. “There’s no way I could’ve stood in front of a class and taught color theory that day.”

For the next 72 hours, Palilonis spent nearly every minute in the newsroom, only returning home to change her clothes and get food. Besides those small amounts of time, she was advising students on what she considers to be one of the most real-life newsroom experiences journalism students have ever had.

“Working with the students was a pretty amazing experience,” Palilonis said. “Having worked in two pretty big newsrooms prior to that, I felt I could bring my knowledge of covering news events in a newsroom to the students and to make it a learning experience for them. I was very proud of the work that they did and felt pretty strongly that they were as talented as any professional I had ever worked with.”

For members of The Daily News staff that year, while working in the newsroom on that day has since become a blur, having the guidance of Palilonis is something people like Smith will never forget.

“The thing I remember the most from that day is Jenn Palilonis just sort of taking control and saying, ‘Look, you need to do this, you need to do this, you need to do this,’” Smith said. “She really helped us understand what we needed to be doing as journalists that day.”

“Full-blown Electricity”

More than just the editorial board of The Daily News crowded into the newsroom that morning, Gubbins said, as junior and senior reporters, and even students who hadn’t stepped foot in the newsroom before gathered, to help report on 9/11.

“We all came together in that editorial meeting room and really just laid it out,” Gubbins said. “The magnitude wasn’t lost on us, but at the same time, nobody knew what was going on. We knew planes hit the twin towers and the Pentagon and that a plane was down in Pennsylvania. We didn’t know who did it, we didn’t know why — none of us did. And the crazy thing is we had to look at it from a college student’s perspective. For all we know, we’re going to war.”

When it came to putting out a paper every weeknight, the staff of The Daily News had a set plan. Each member of the team knew what to do, but, Smith said, this print night was full of unknowns.

“The Daily News is sort of this machine that runs on repeat,” Smith said, “but not on that day, because none of us had ever seen something like this before.”

For a team built entirely of college students, some of which had no prior reporting experience, Gubbins said, more than just the reporting process was on their minds.

'Is the military draft about to be implemented again?' they wondered.

No one had the answers, but as a team of student journalists, Gubbins said, it was their job to find them.

“It was an effort where everyone contributed, and everyone brought their A-game,” Gubbins said. “If you look at that edition [of The Daily News], there’s barely any wire copy in there. It’s almost entirely produced by us.”

But, Werner said, the reporting process wasn’t easy. There was no social media feed to keep track of the events unfolding and nowhere to turn to find sources who could contribute to the reporting of that day by providing eyewitness accounts. For the staff of The Daily News, it was all hands on deck.

“We gathered a lot of our information from the morning shows,” Werner said. “I remember having the "Today" show on. We were writing and calling people and gathering quotes. It was just a different time.”

While there was plenty of information available from different news outlets, Werner said, the challenge was finding a way to localize it and make it suitable for the Ball State and Muncie audience. Werner took a man-on-the-street approach to her story that day, interviewing faculty and students around campus to get their reaction to the event and localize her angle.

“I went out and just started talking to people,” Werner said. “There was no rhyme or reason to how I talked to people because, on that day, everybody was affected. I just framed it in the context of, ‘This is one of the events you’re never going to forget where you were when you heard the news.’ I just wanted to capture what faculty and students had to say of how shocked they were.”

While The Daily News had access to the Associated Press (AP), Gubbins said the staff was limited on their access to photos. But, after a call with the AP bureau in Indianapolis, the team received free access to all photos taken and published by AP that day.

“There were thousands of photos,” Gubbins said, “some of which have probably never been printed. I was seeing live photos come in through the photo wire — people falling from the sky, body parts, just horrific images. And it took a toll on me a little bit — those were some of the most graphic, just emotionally heavy images I’ve ever seen.”

The newsroom at the time was nearly half the size as it is now, Werner said, but it was a “constant flurry of people in and out” as the team worked on piecing together what has since become a historical edition of The Daily News.

“It was full-blown electricity,” Gubbins said. “Everybody was working. I’ve never seen us do so many rewrites. People wanted their copy top-notch, the photographers wanted their images perfect. The designers — oh my God, we blew up that front page probably five times. It had to be right.”

Besides the editorial board, Gubbins said, people were constantly stopping by the newsroom with questions about what had happened, story leads to follow and updates on the events unfolding. Without social media, there was nowhere else for people to go.

“I’ll never forget — there was a kid that came running into the newsroom hysterical,” Gubbins said. “He kept saying, ‘Oh, my god! They got Dayton! They got Dayton!’ He was on the phone with his girlfriend, who was a student at the University of Dayton. All of a sudden, he heard an explosion, and his girlfriend’s phone went dead.”

While scrambling to help his team, Gubbins said, he made a phone call to the Ohio State Police out of Dayton. As a newspaper editor, he said, he knew he had to follow up on any lead that came through the newsroom doors that day.

The Wright-Patterson Air Force Base is located just east of Dayton, Ohio, and to help fight the hijackers, the base deployed a handful of fighter jets. The planes broke the sound barrier.

“We had people in the newsroom that were ready to go,” Gubbins said. “Dayton’s an hour or two away from Muncie, and they were ready. They were ready to hop in the car and go. We were kids, we were scared, but we all wanted to be the most professional journalists we could be.”

“Freedom Under Fire”

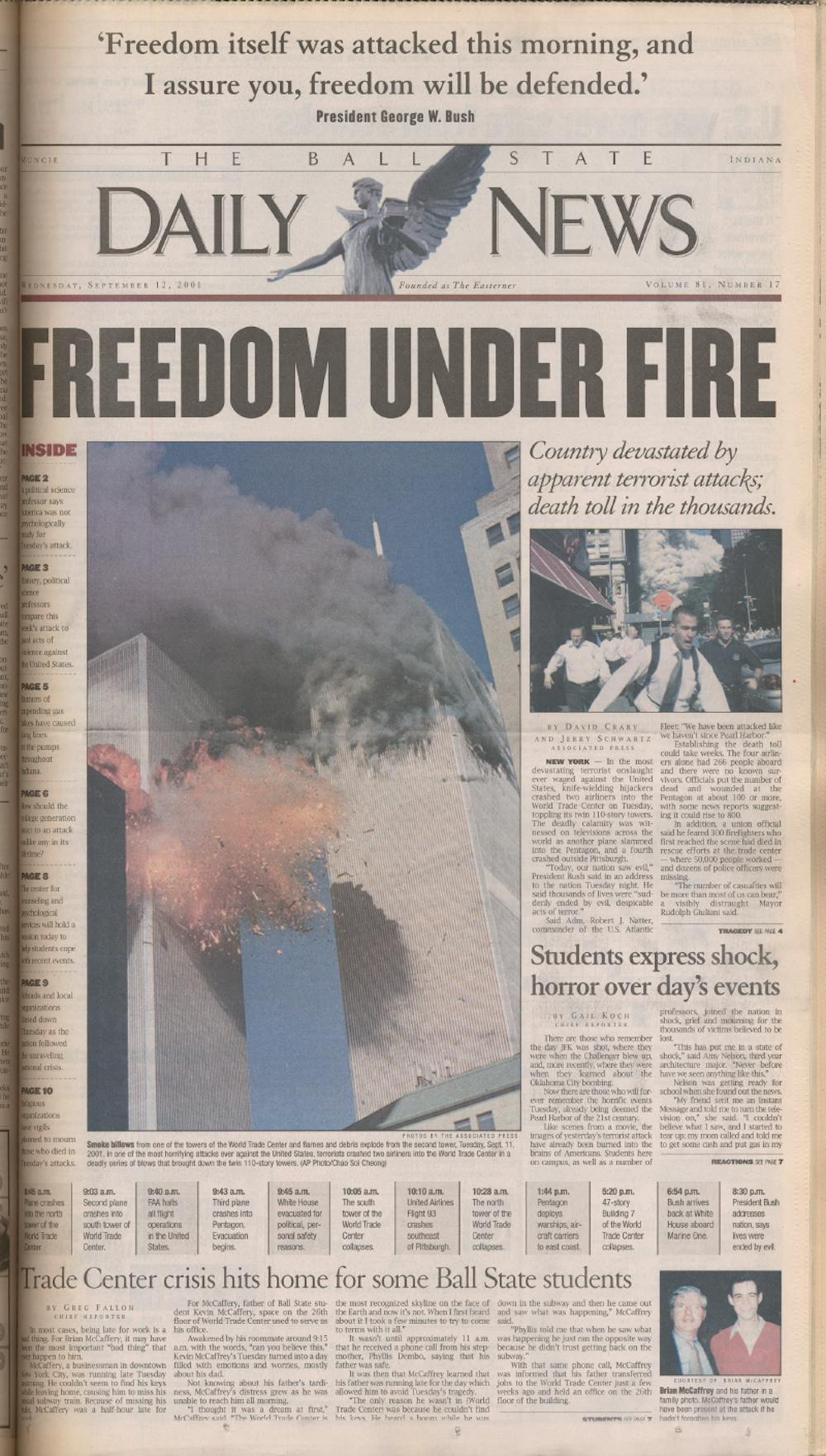

The process of putting together what has since become a legendary cover page of The Daily News, Gubbins said, was one that required effort from the entire team, as the cover was redesigned half a dozen times before being sent to the printer late that night.

“I don’t remember who came up with ‘Freedom Under Fire,’” Gubbins said, “but what we loved about that was that no one else did it. There were all kinds of newspapers where everybody kind of did the same thing. Ours was reflective, but it told the story.”

Smith was on the design team that night, working closely with Palilonis and other members of The Daily News on a front cover that had gone through dozens of changes throughout the day.

“We asked ourselves, ‘What is this headline saying? What is the mix of stories here?’’’ Smith said. “I remember working a lot on the graphic for it, trying to figure out what needed to be in there, but there was endless discussion on what that headline would mean.”

At that point in the day, The Daily News staff didn’t know much besides planes being hijacked and the World Trade Center coming down. The number of people who had died, “the bigger story that we sort of take for granted in knowing today,” Smith said, was still unclear.

For Smith , having the guidance and help of Palilonis in his design process is something he didn’t take for granted.

“Jenn hadn’t been through 9/11, but she had been through big news before, and her experience as a journalist, and her ability to help us shake out of the moment and focus on what needed to be done, I think, was what was very valuable there,” Smith said. “From a design standpoint, we knew the mechanics of what to do, but Jenn really just helped us focus in and work through the journalism and through the stories and through the framings and put it all together.”

On the morning of Sept. 12, 2001, students all around campus were carrying the 9/11 edition of The Daily News in their hands with the headline “FREEDOM UNDER FIRE” in bold, black letters across the top of every front page.

It was surreal, Werner said, seeing nearly every person who walked past her carrying the newspaper she had worked until midnight to make possible — a paper which, on a normal morning, was only carried by a handful of students.

“The front cover of that issue is seared into my brain,” Werner said. “It just reminded me of the role of the press and how important what we do is to people. We’re the eyes onto what happens, even from this far out.”

For Smith, he said, walking around campus that day and seeing students with the paper in their hands made him realize that his work “does matter.”

“That was my first experience of one of those really big news days,” Smith said. “Seeing that the next day — it was incredibly gratifying.”

The Newseum in Washington, D.C., archived and compiled more than 100 newspaper front pages from Sept. 12, 2001. The Daily News was one of the only college papers on display. Later, the Society of Professional Journalists compiled a book of front covers for Sept. 11, and The Daily News’ cover was included.

“It was interesting as a student to go and look through the Newseum and see how other papers had covered it,” Smith said. “I said, ‘All right, I think we got this stuff right.’”

For Palilonis, looking back at the success of the Sept. 12, 2001, edition of The Daily News “shows how incredibly talented they all are and were.”

“We’re not talking about professional journalists who’ve had 20 years of experience covering hard stuff,” Palilonis said. “We’re talking about 20-year-olds who have never done anything like that before, and the fact that they rose to the occasion and did such impressive work, so much so that it was recognized by other journalists — that’s pretty impressive.

“I think it just speaks volumes about how committed they were to their craft and how mature they really were to be able, in that moment, to cut through the grief and the devastation and fear that we were all feeling that day and do a job so well,” she said. “I think that’s a pretty amazing thing for any journalist to say they’ve done, let alone a bunch of kids.”

“In our blood”

While Palilonis couldn’t be in the Chicago Sun-Times newsroom reporting on the events of that morning, she took it upon herself to make The Daily News her newsroom for the next three days, advising and guiding the staff members through the process of covering hard news.

If there was ever a doubt in her mind that teaching was something she was meant to do, Palilonis said, the events of Sept. 11, 2001, “certainly solidified it for me.”

“It didn't really matter to me that I wasn't the one doing the reporting,” she said. “I think that what was significant for me is that I was able to share my experience and my knowledge of how a newsroom works with students in a way that is different from the average, everyday operation of a student newspaper.”

Reflecting on the events of that day, Gubbins, Werner and Smith are all grateful for the help Palilonis provided during the process of piecing the Sept. 12, 2001, edition of The Daily News together.

“I think, without her that day, we would have been a bunch of shell-shocked kids wandering around the newsroom trying to figure out what to do,” Smith said. “She really led the way for us in one of the most impressive displays of teaching I have ever seen.”

Smith said having the opportunity to have worked in a newsroom with so much potential for learning and growth is one he will never take for granted, especially having Palilonis as a mentor.

“I love the fact that I went to school at a place that gave us the opportunity to practice and to learn at that level,” Smith said. “I don't think that every journalism student in the world gets the kind of opportunity that we got that day.”

If the staff of The Daily News that year were to have a reunion, Werner said, the first and only thing they would talk about is putting that edition of the paper together. It was a paper, Gubbins said, that they likely all still have copies of, tucked away somewhere in boxes or on their shelves.

“It's one of those editions that you wish you never had made,” Smith said. “It’s not a part of history that I think anyone wants to celebrate or repeat, but I am grateful for the group of people, especially, that we got to put that out with and work with that day, and Jenn for her guidance.”

Putting the paper together, Gubbins said, “brought the absolute very best out of everyone on that staff.” To this day, he said, it “blows [him] away” how a handful of students took “every ounce of professional journalism” they had within them to bring that paper to fruition.

Each and every one of them, Palilonis said, left the newsroom changed and with a better understanding of what it means to be a journalist.

“Our jobs as journalists are to cover the story, no matter how hard it is personally or professionally,” Palilonis said. “It’s in our blood to do that. There's really no other place for you to be. You have to be in the newsroom and bring the news to life. It really is in our blood.”

Contact Taylor Smith with comments at tnsmith6@bsu.edu or on Twitter @taywrites.