Events during the Oklahoma City bombing

April 19, 1995: A 4,800-pound bomb made of fertilizer and fuel oil packed inside a rented Ryder truck exploded in front of the Alfred Murrah Federal Building.

90 minutes after the bomb went off, an Oklahoma State Trooper arrested Timothy McVeigh for driving without a license plate and carrying a concealed weapon.

April 20, 1995: Merrick Garland arrived in Oklahoma City to lead the FBI investigation and supervise the prosecution cases against McVeigh and accomplice Terry Nichols.

April 21, 1995: Federal authorities arrested McVeigh on probable cause connecting him to the bombing. Nichols surrendered to authorities.

Aug. 11, 1995: A federal grand jury indicted McVeigh and Nichols on murder and conspiracy charges.

Feb. 20, 1996: Chief U.S. District Judge Richard Matsch moved the case to Denver because of pretrial publicity.

June 2, 1997: A federal jury in Denver convicted McVeigh on 11 murder and conspiracy counts. He was later sentenced to death.

Dec. 23, 1997: Nichols was convicted of conspiracy and involuntary manslaughter, aquitted of weapons and explosives charges, He was later sentenced to life in prison without parole.

March 29, 1999: Oklahoma County District Attorney Bob Macy charged Nichols with 160 state counts of first-degree murder and said he will seek the death penalty. Another count involving the death of a fetus was added later.

Jan. 31, 2000: Nichols was moved from Florence Federal Correctional Complex in Florence, Colorado to Oklahoma City to face state charges.

June 11, 2001: McVeigh was executed by lethal injection in Terre Haute, Indiana.

May 26, 2004: Nichols was convicted of 161 state murder charges. Jurors could not come to a unanimous decision regarding the death penalty.

Source: Associated Press and FBI

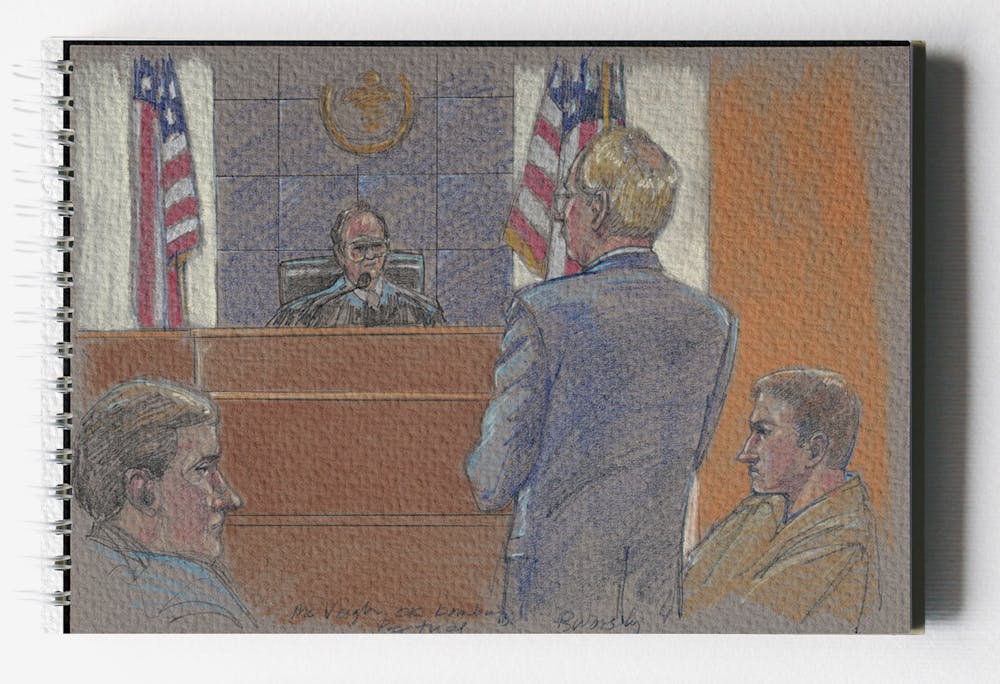

The courtroom was full every day — standing-room-only full.

Journalists filled every available chair, leaving members of the public to crowd in where they could for a trial that weighed heavily on the nation.

It was 1997, and Terry Nichols stood accused for the role it was believed he played in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing that killed 168 people — the worst act of terrorism on U.S. soil prior to the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

Tension was high for prosecutors, who felt a great deal of responsibility in representing the United States. At least, that's how Ball State President Geoffrey Mearns remembers those days.

“It was a very complex case — one of the most complex prosecutions in our nation’s history,” he said. “It, in essence, was a murder trial with the families of 168 different victims.”

Nichols was an accomplice to Timothy McVeigh in a bombing at the Alfred Murrah Federal Building April 19, 1995, that killed 168 people, including 19 children. Nichols was convicted of conspiracy and eight counts of involuntary manslaughter Dec. 23, 1997, according to the U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General.

Mearns was one of three principal trial lawyers in the federal case against Nichols. He was about 10 years into his legal career as a prosecutor when Beth Wilkinson, a former classmate from the University of Virginia, recommended he be considered for a role on the federal prosecution team. Wilkinson had already been on the prosecution team against McVeigh and thought Mearns would serve the case against Nichols well.

“We had been assistant U.S. attorneys together in New York,” Wilkinson said. “I knew him from law school, and I knew him to be an excellent lawyer.”

Mearns flew to Denver to interview with other members of the prosecution team and Merrick Garland. Now, Garland is President Joe Biden’s nominee for U.S. attorney general, but back then, he was the associate deputy attorney general.

“That’s when I met [Garland], and it was based on his recommendation to Attorney General [Janet] Reno that I was selected and appointed to serve,” Mearns said. “Judge Garland was our liaison from our offices in Denver to the attorney general’s.”

Inside the courtroom

Though Nichols was at his home in Herington, Kansas, when the bomb went off, the prosecution team linked receipts, coded letters and McVeigh’s getaway car to Nichols. Witnesses also reported seeing the Ryder truck that contained the bomb at a lake in Kansas, where McVeigh and Nichols allegedly built the bomb together, The Associated Press reported at the time.

Mearns specialized in presenting forensic expert testimony connecting plastic fragments found in the bomb rubble to drums Nichols owned. He also heard statements from victims' family members.

“On a regular basis, the testimony from those families and the survivors was introduced for various reasons as part of the evidence in the case,” Mearns said. “The emotions were, at times, almost overwhelming.”

Mearns said the judge insisted lawyers for the defense and prosecution maintain composure in the courtroom, which was sometimes difficult. While working on the case in Denver, he said, he was more than 1,000 miles away from his wife, Jennifer — who was pregnant at the time with the couple’s twins, Geoffrey Jr. and Molly — and their other three children, Bridget, 6, Christina, 4, and Clare, 1.

“It was difficult to hear the testimony of a mother whose 4-year-old daughter was killed — who was looking forward to the day when she could take her daughter to her first day of kindergarten and how she would never be able to do that,” Mearns said. “You couldn’t help hearing these stories without thinking about what it would be like if that had personally had an impact on you.”

The path to prosecution

Amy Beckett, Ball State assistant teaching professor of criminal justice and criminology, said the Oklahoma City bombing changed the way some Americans thought about terrorism.

“I think this case was the first time that we accepted the fact that it could be our own people that are terrorizing our own citizens,” she said. “I remember thinking after 9/11, ‘How do we know this wasn’t domestic terrorism like Oklahoma?’”

Beckett said she knew someone involved in the forensic evidence investigation in Oklahoma City.

“I had a friend who had a cadaver dog over there, and they had to find dead bodies,” she said. “They said the dogs were getting so depressed that the firefighters had to hide and pretend to be recovered so the dogs would be motivated to continue to look.”

Garland led the evidence investigation of the Oklahoma City bombing and supervised the prosecution team for the cases against McVeigh and Nichols.

When former President Barack Obama nominated Garland for a seat on the United States Supreme Court March 16, 2016, he praised Garland’s dedication to ethics and the rule of law in the Oklahoma City case in a Rose Garden ceremony at the White House.

“Throughout the process, Merrick took pains to do everything by the book,” Obama said during a press conference he called to announce his nominee. “When people offered to turn over evidence voluntarily, he refused, taking the harder route of obtaining the proper subpoenas instead, because Merrick would take no chances that someone who murdered innocent Americans might go free on a technicality.”

The Senate Judiciary Committee, controlled by Republicans in 2016, refused to hold a hearing for any Supreme Court nominee until after the 2016 presidential election. When Garland came to the Senate floor for his hearing for attorney general, he received positive comments from Democrats and Republicans.

Chuck Grassley, Republican senator of Iowa and former chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, told Garland Feb. 22 during his hearing, “I respect you, and I think you are a good pick for this job.”

‘Driven by a desire to serve’

Mearns said Garland is an admirable appointment for attorney general, especially because of his experience as a prosecutor for the Justice Department and as a federal appellate court judge. He said Garland embodies qualities of servant leadership.

“He’s thoughtful, and he’s modest, even to the point of being humble,” Mearns said. “Here’s somebody who has had an extraordinary career, had a great deal of responsibility and authority, but is at his core modest, and humble and driven by a desire to serve others and to serve the interest of justice on behalf of every member of our country.”

In his Feb. 22 Senate confirmation hearing, Garland said investigating political extremists and domestic terrorists will be his first priority if he is confirmed.

Because of the increased use of social media that can be used as communication platforms for political extremists, Garland said, “We are facing a more dangerous period than we faced in Oklahoma City.”

Garland mentioned that FBI Director Christopher Wray has said white supremacists pose a domestic terrorism threat. Mearns said for students born after the Oklahoma City bombing, 9/11 likely shaped their understanding of terrorism.

“We know now that the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security say the biggest terrorism threat in our country right now is not international terrorism … it’s domestic terrorism,” Mearns said. “It’s very important for us to reflect on what happened in the period that led up to the Oklahoma City bombing so that we do all in our power to be sure something like that never happens again.”

As a prosecutor, Mearns estimated he was personally responsible for a couple hundred convictions and served supervisory roles for a few more hundred cases.

Mearns left legal practice to pursue administrative roles in higher education in 2004, serving as the provost of Cleveland State University and president of Northern Kentucky University before coming to Ball State in 2017.

“Do I miss occasionally an argument or being in court? Sure. It was rewarding and exciting,” Mearns said, “but no regrets because I really enjoy very much the rewards of what I get to do now.”

Contact Grace McCormick with comments at grmccormick@bsu.edu or on Twitter @graceMc564.