The Middletown Studies

Russell Irving, Keith O’Neal, and Bibi Bahrami call Muncie home. Their experiences are vastly different, but share one thing in common: they’ve been left out of a national narrative. One that’s defined Muncie for decades.

In the 1920s, Robert and Helen Lynd published their first collection of surveys and other sociological studies in their book “Middletown: A Study of Modern American Culture.” This 500-page study examined the lives of individuals living in what the Lynd’s considered an average American town, but some perspectives were left out of its pages.

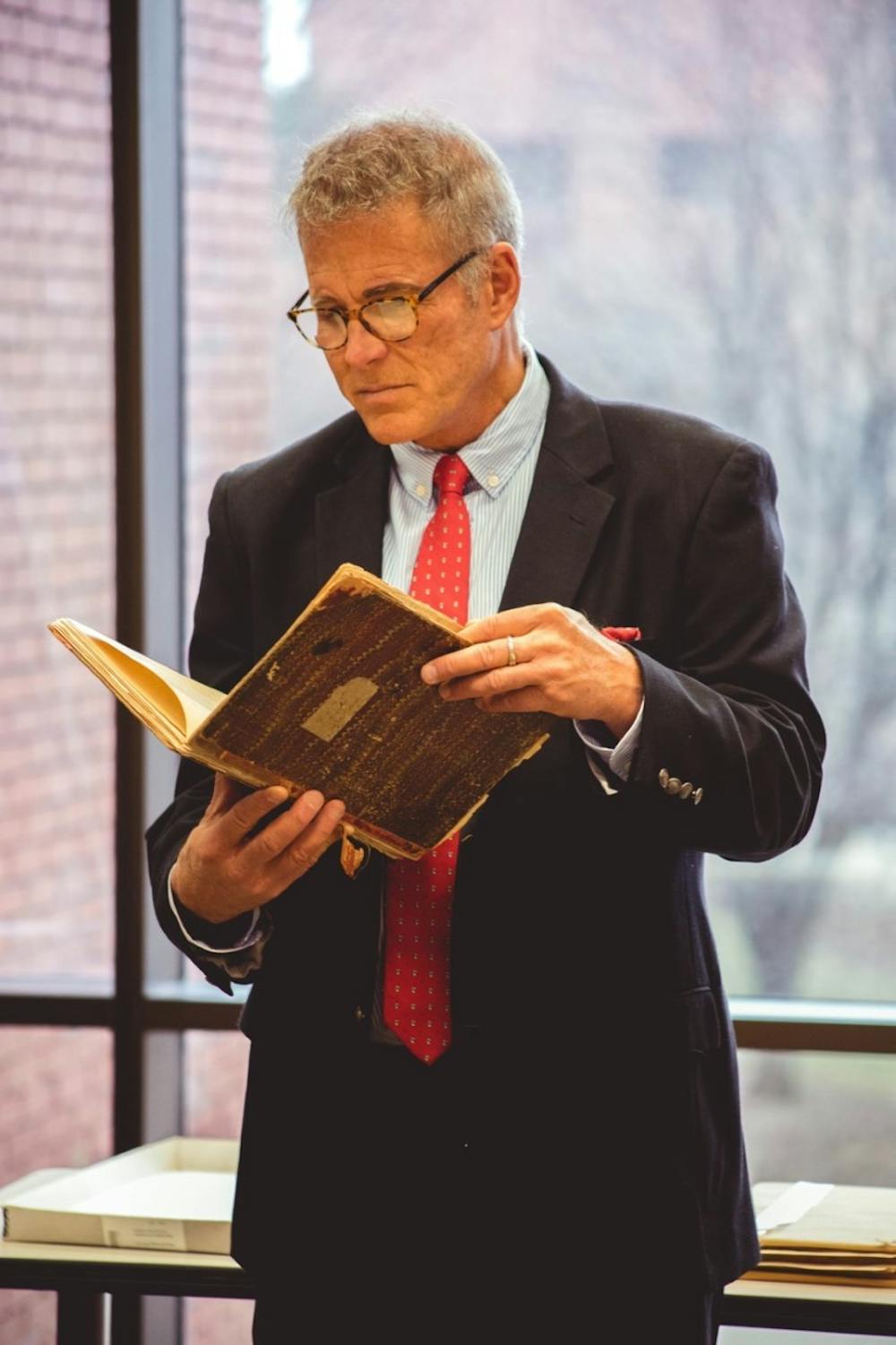

“Robert and Helen Lynd wanted to focus on relations between the ‘business class’ and the working class,” says James Connolly, director of the Center for Middletown Studies. “To do that, they tried to eliminate other variables, such as racial or ethnic differences. They picked Muncie as a place to study in part because they thought it was a homogenous place. That approach was a mistake since class can’t be easily separated from race, ethnicity, religion, or other categories.”

The Lynd’s study would soon be celebrated as a triumph in the world of sociology. Middletown would go on to symbolically represent the attitudes and actions of middle America for years to come. Even today, Muncie is viewed by many as a typical American town, all thanks to the data gathered by the Lynds.

The Lynd’s decided to perform their studies on the residents of Muncie, Indiana, because they believed the town had a “small African-American and foreign-born population.” Their surveys and data left members of the Muncie community out of their research as they only surveyed “civilized, white Americans.”

“The one thing I think deserves more attention is the ways in which Muncie was and is diverse,” Connolly says. “Outsiders tend to think of [Muncie] as filled with white, blue-collar people and little else. That’s true to some extent, but there is more variety when you look more closely at the city’s history and present character.”

At the time of the Lynds’ study, there were many citizens outside of their parameters. Today, as many people still look to Muncie as a hallmark of the midwest, there are missing perspectives that walk by everyday. Perspectives that live in Muncie neighborhoods, have memories of Muncie childhoods, have loved and lost and persevered, and who are just as much a part of Muncie as the Middletown subjects. The only difference is that they are largely forgotten by the wider world, overshadowed by the results of Middletown.

Russell Irving, Bishop Keith O’Neal, and Bibi Bahrami are just three of the many perspectives that weren’t represented in the Middletown studies.

Russell Irving

Russell Irving sits in the library of The Neely House. The house was originally built in 1852, and Russell is proud to share its history through the restaurant. The Neely House, Photo Courtesy

Russell Irving runs his fingers over the spines of old novels in The Neely House’s library, pointing out how each one was cut from the book it once belonged to and laughing as he described it as “the world’s largest collection of short stories.”

The library is on the back wall of one of the dining rooms in The Neely House, which Russell, with the help of a few others, decorated and remodeled himself.

Russell is the owner of The Neely House, a restaurant that is modeled on Thomas S. Neely, a Muncie pioneer who kept extensive journals about life in the 1800s. The Neely House recreates life as it might have been during this time and serves historically accurate food. Russell is proud of what he offers Muncie, a classic and historical artifact of the town’s past and a place for Muncie residents to enjoy the “No. 1 brunch in Indiana.”

Muncie has always been home for Russell, and he’s most comfortable at The Neely House. He gives a spontaneous tour of each individual room, explaining what it was used for in the house’s earlier days, and grinning widely as he shares his extensive knowledge of Thomas Neely and his relation to Muncie history.

Muncie is where Russell’s family is, where his life with his husband, Ean Taylor, grows and thrives, and where his prized restaurant continues to succeed.

The Neely House is located at 617 E. Adams St. in Muncie, Indiana. Taylor Smith, Ball Bearings

Russell Irving looks through the books in the library of The Neely House. Taylor Smith, Ball Bearings

The food served at The Neely House is historically accurate for the time period in which the house was built. Taylor Smith, Ball Bearings

The house was originally built in 1852. Taylor Smith, Ball Bearings

But Muncie didn’t always bring Russell a sense of satisfaction and belonging. Growing up as a gay man in Muncie during the 1960s and 70s made acceptance hard to come by.

Russell started having feelings that something was different about him when he was younger. It was the 60s in the Midwest, and Russell didn’t have many resources to turn to as a way to explore what he was experiencing. So he did what most children his age would do: he turned to his mother.

How come whenever two people get married it’s always one man and one woman, and it’s never two men or two women? Russell asked her.

“I remember she just went crazy. She just went sick and twisted, so all I remember is, ‘wow, there’s a lot more to that question,’” he says.

But the answer he received didn’t stop Russell from continuing to wonder. As he hit puberty, the answer to his questions became clearer, but it didn’t make his life any easier.

“I realized I was different by things that were out of my control,” Russell says, “and there was just a huge amount of shame.”

Because of this, Russell experienced discomfort throughout high school. He doesn’t remember that period of life fondly because of the internal struggle he experienced.

“I thought about suicide many times as a teenager,” Russell says. “I prayed every night from the time I was 13 to 17 for God to take the things out of my head that were in there.”

But the things in Russell’s head never left, and he remembers crying and praying, telling God, “This can’t be right. You’ve got to fix this.”

At 17 years old, Russell accepted that the thoughts weren’t going away, so he decided he would get as far away from his family as possible to save them shame. Russell moved to Los Angeles for college where he studied animation at California Institute of the Arts.

But leaving Muncie didn’t mean leaving behind the part of him Russell felt ashamed of; it meant trying to figure it out. Russell made plans to get a psychiatric evaluation to “get fixed,” but his psychiatrist had other knowledge to share.

His psychiatrist told him that being gay wasn’t a mental illness; Russell’s real problem was that he grew up in a community that was unaccepting.

Russell Irving (left) with husband Ean Taylor (right). Russell and Ean are the co-owners of The Neely House restaurant. Russell Irving, Photo Provided

Russell began what he calls his exploratory phase of his life at that point, trying to build himself in the Los Angeles culture he was immersed in. His first step was self-acceptance and surrounding himself with people who accepted him. He made friends, and even had his first boyfriend.

“To be around people who accept you is so comforting and so addicting,” he says.

While still in California, Russell’s mother called him and asked if he and his boyfriend were living together. That phone call is when he officially came out to his parents. He was 22.

Are you kidding? She asked.

You call me from 2000 miles away to ask me this, and you think I’m kidding? Was Russell’s reply.

A big struggle of coming out, Russell said, is that he wanted the comfort of hearing other people tell him that he was okay. But the real struggle is being able to tell yourself that you are okay, and sometimes Russell had to do that even when other people told him the opposite.

“At the end of the day, you have to put your head on your pillow and believe that you’re okay.”

Russell Irving examines a book in Ball State University’s Bracken Library. Russell Irving, Photo Provided

Today, living in Muncie again with Ean, who Russell considers “the single greatest human” he knows, Russell knows that he is okay. He never thought he would live to see the advent of things like “Will and Grace,” marriage equality, and acceptance in books, movies, and T.V. shows, but he is happy for the kids who are able to grow up in an environment more accepting than the one he grew up in.

“I think it’s great that we have gotten to that place, but I think Muncie still struggles,” he says. “I still have people who don’t care for me and think that [being gay] is a lifestyle that was chosen. They don’t understand. Ignorance is rampant.”

Being gay, Russell said, is synonymous with having no moral compass for some people, and Russell thinks this is because there is a huge shortage of critical thinking. People find comfort in following rules and religious norms, he says, and they don’t use critical thinking to search for the whole truth.

Russell hopes more people start thinking critically, but he is not one to protest with signs and march in the streets. He understands that he has done his part, and that society as a whole is what needs to continue to change.

“I can’t fix people that are broken. I can’t fix the way people think. I can just simply live by example. And that’s always been my activism. I live a life I’m proud of, and if people learn something from it, that’s their choice.”

Bishop Keith O’Neal

Keith O’Neal, the founder of Destiny Christian Center. Keith O’Neal, Photo Provided

Keith O’Neal sits in front of one of the large windows in the conference room of Destiny Christian Center International, the light from outside illuminating his already glowing smile.

Keith has spent all but three years of his life in Muncie. At 59 years old, he has established his own church in his hometown and built what he considers the “most diverse church community” in Muncie, and he believes that throughout his life, God prepared him for the job.

Despite being a pastor now, there was a time in Keith’s life when his faith in God was tested.

There were times where he doubted God and the plans he had for Keith and his family. When he and his wife divorced after 15 years of marriage, the two spent 18 years apart. During that period of time, Keith questioned moving out of Muncie and possibly changing his career path.

It seems like you’re leaving me here, Keith would say to God. Are you trying to kill me?

“I went through some very dark times when we got divorced,” he says. “Even some poverty issues that I had never experienced before. My parents were considered well-off, and then all of a sudden I found myself lacking.”

Keith’s parents were both involved in the education system growing up. Their jobs were very different from most black families Keith knew at the time, and because of this, he found himself “navigating both worlds” in terms of class and race.

Growing up, most, if not all, of his friends were white, and despite being one of the only black families in Halteman Village, his friends were all very accepting of him and his family. But his experience was culturally different from other black families living in Muncie during the 70s.

Keith says that he remembers a divide between Muncie’s business class and working class during the 70s. Most of his black family friends, as well as people who were not exclusively black, he remembers, were part of the working class at that time.

Struggling after his divorce, and grappling with money issues for the first time in his life, the Muncie that Keith had known suddenly seemed very different. But Keith says he knew God was teaching him important lessons during that time of his life.

“There was a whole lot of softening of some really prideful attitudes that I had, which actually helped to qualify me for what I’m doing now,” he says. “I never could have pastored in that shape.”

Keith says he was called to pastor. After his encounter with God when he was 22, he knew by the time he was 23 that he would be a pastor, but he didn’t become one until he was 45 years old.

“It was a call. It was time, and I just knew in my heart it was time to launch [Destiny Christian Center],” he says. “There was nothing good about the timing at all, but it was a call.”

Keith O’Neal delivers a sermon at the Destiny Christian Center. The church started in Keith’s living room with eight people and has grown to a membership around 400. Keith O’Neal, Photo Provided

The church, which started as an eight-person team in Keith’s living room, could have been established anywhere. Keith says he had lots of options, but Muncie has always been his home.

“I feel called to Muncie. It’s really that simple. I love Muncie, and that’s why I stay.”

Today, Destiny Christian Center’s membership is around 400 people on average, and nearly half of its community is composed of individuals who would not have been included in Muncie’s Middletown Studies.

“We’re a very community-oriented serving church, and we are arguably the most diverse church in our city,” Keith says. “Out of those people who attend regularly, it’s probably 45% African American, which is very rare in this nation, and even more rare in this region, especially with a black pastor.”

“If you don’t have the voices and the representation around the table and in the decision-making processes, you just continue to leave people out,” Keith says. “I’ve been [in Muncie] forever, and what is very obvious is that black people have just been left out of the decision-making process. You have very few black people that are in the position to make decisions that would affect those that look like them.”

For Keith, improvement begins with intentionality. People have to want change in order for change to happen, he says. Everyone’s voice needs to be heard, and there has to be intention to make that happen.

The Destiny Christian Center is located at 5000 E. Centennial Ave. in Muncie, Indiana. Emily Wright, Ball Bearings

When Keith reads the Bible, he says he cannot not read it as a black man. He reads the story of the Exodus from the perspective of the oppressed, but others who are different from him may not read it the same way, and crucial perspectives are therefore ignored.

“We need to be willing to hear things from another perspective. We need to get that experience of what it might be like to be someone else,” Keith says. “We live in an adversarial nation, and so it’s impossible to get the best product [of society] because we spend all of our time trying to tear each other down.”

The bottom line, Keith says, is that we all need to come together to figure out how to make sure everyone is taken care of and heard, and that’s the message Keith lives every day as he walks through the doors of Destiny Christian Center, ready to welcome anyone into his community with open arms and a glowing smile.

Bibi Bahrami

Bibi Bahrami sits in her office at the Islamic Center. As the president of the center, Bahrami says she pushes for greater involvement within the Muncie community. Jacob Musselman, Ball Bearings

Unlike Russell and Keith, Bibi Bahrami didn’t grow up in Muncie. She didn’t grow up in the United States, either. She is a refugee from Afghanistan, and she made Muncie her new home in 1986.

Bibi left her home when she was just 13 years old with nothing but her traditional clothing after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979. She spent the next six years of her life volunteering at the refugee camp in Pakistan, where she met Saber Bahrami, another volunteer. The two fell in love and got engaged.

Life at the refugee camp was hard. Her memories while in Pakistan involve fighting for survival in the refugee camp and losing her loved ones, including her brother and grandfather.

“The experience in the refugee camp was always hearing the bad news that somebody has killed somebody else,” she says.

They stayed at the camp while Saber searched for a place to do his medical residency in America. After searching for employment for five years, Saber was offered a position at Ball Memorial Hospital.

“That’s how I was able to come here. Muncie became my first home, more than Afghanistan,” Bibi says, “I love my beautiful Muncie.”

Bibi Bahrami stands outside the Islamic Center of Muncie on March 15, 2020. The Islamic Center is located at 5141 W. Hessler Road in Muncie, Indiana. Jacob Musselman, Ball Bearings

But the adaptation to Muncie wasn’t easy. Bibi felt isolated and alone in her new city. When she travelled outside of her house alone, she carried a sign with her that said “I don’t speak English.”

One day, Saber reached out to their neighbors, Elizabeth and Olive Mock, in the apartment he and Bibi shared. He asked them if they could visit his wife.

Elizabeth and Olive would visit Bibi and help her with her studying, she says, teaching her English, playing games, and going to church and out to lunch together. Bibi considered them family.

Elizabeth and Olive played a big role in Bibi beginning to feel like Muncie was home.

“They’re welcoming — the people of Muncie — in how they accommodate, how they comfort, how they assist me,” Bibi says. “The people who started with me, supporting me, they’ve stood beside me. It means the world to me. There’s no place like Muncie. I always say that, wherever I go. Muncie love is special.”

Bibi attended a GED program to earn her high school diploma after moving to Muncie. She later began her college career at Ball State University, where she studied accounting, but after founding her own non-profit organization, Afghan Women’s and Kids’ Education & Necessities, Inc. (AWAKEN), she chose to change her major to art instead.

Bibi says she founded her organization after 9/11 when she believed there was still some home left for Afghanistan to rebuild. She always had a vision to start an organization after completing school and raising her children, but 9/11 presented her with an opportunity that she knew she could not ignore.

After the United States began attacks on the Taliban on Oct. 7, 2001, Bibi knew her loved ones were being affected. She had already lost some of her loved ones from the Soviet invasion, she said. After 9/11, she lost even more.

“One day, my parents were crying, I was watching the news crying, and I said ‘Enough. Enough is enough. I’m just so exhausted over this.’ I turned off the T.V. and said, ‘I’m not going to watch it anymore. I’m going to do something about it.”

Bibi says that because the women and children suffered so much during Soviet occupation, she wanted to reach out to that population and help them in the areas in which they were suffering most: healthcare, education, and vocational training.

“I wish that one day I can give this to the girls I left behind who had a similar thirst for education.”

Bibi Bahrami, president of the Islamic Center of Muncie receives Ball State’s 2019 Community Partner of the Year award from President Geoffrey Mearns. The Islamic Center of Muncie was given the award after partnering with Ball State students and a professor to produce a documentary that told the stories of individuals within the Muslim community in Muncie. Ball State University, Photo Provided

As Bibi became more involved in helping people in her home country, her commitment to the Muncie community also grew stronger. Bibi ended up finding a diverse Muslim population in Muncie. She gets together with them to celebrate holidays.

“It’s been a great experience the last 30 years with these people,” Bibi says. “It’s been a blessing.”

Bibi and Saber were always involved in the Islamic Center of Muncie, where Saber served as president for around 10 years. Bibi began to add women representation to the community, and she now serves as the first female president of the Islamic Center of Muncie after over 40 years of the center’s existence.

“I added a woman’s touch to it,” she says.

Bibi says she made it her mission to get the Islamic Center more involved with the greater Muncie community.

“I am one of those to always break the ice, and that has been a big part of my life,” Bibi says. “I like connecting people in the community.”

When it comes to Middletown, Bibi says that by leaving people out, we are not doing a favor for our people.

Bibi Bahrami is the first female president of the Islamic Center of Muncie. Jacob Musselman, Ball Bearings

“I strongly believe in education, opportunity,” Bibi says, “and if these [studies] are going to give education and opportunity to others, they need to be well-rounded.”

Students at Ball State, Bibi believes, not only need to study their academics, but they need to know more about Muncie, its history, and its people.

“There’s a Middletown whether you’re Muslim, whether you’re Jewish, whether you’re Hindu, whether you’re Buddhist,” Bibi says. “There are different people, nationalities, religious groups, and they all have a Middletown.”