Editor’s Note: At the request of the Youth Opportunity Center (YOC), for privacy and safety reasons, The Ball State Daily News did not interview residents, which is why there are no quotes, photos or information identifying them.

CHAPTER 1: Relating to stories

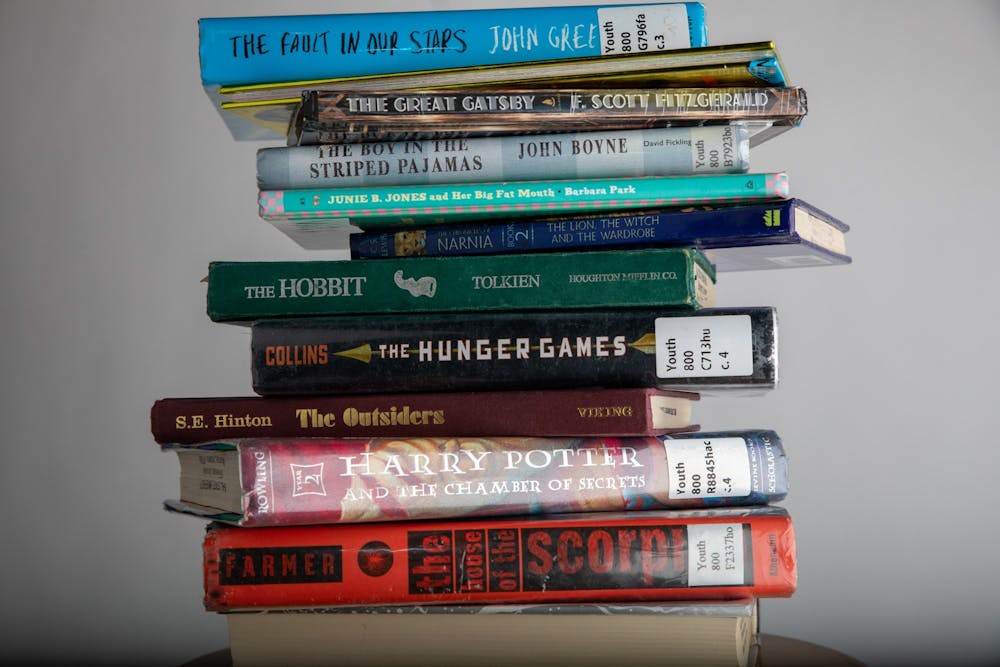

There’s Sarah, whose mother tries to drown her; Bruno, who sneaks into a concentration camp to help a Jewish boy; and Katniss, who volunteers to take her sister’s place in an annual event where 24 kids fight each other to their deaths.

Every story lining the thin, metal shelves of a gray cabinet at Muncie’s Youth Opportunity Center (YOC) follows the life of a fictional character who experiences trauma. With each flip of a page, the novels provide inspiration and hope about overcoming obstacles to residents at this treatment center.

But only to those who can read them.

More than 200 children ages 13-17 live, learn and undergo treatment at the YOC, which has cared for Indiana’s “troubled children” for the past 25 years. Because of family trauma, foster care issues or mistakes of their own, these residents wrestle with their academics. Some have never even held a book, said Ashley Williams, director of program services.

“We know our kids are at a significant disadvantage educationally, so when they come into placement, we know they are already behind,” Williams said. “They are struggling, and they often don’t have confidence in themselves … They can be several grade levels behind where they should be as far as reading and math, but we are bound [to teach them at the] grade level they are admitted.”

YOC Campus Map

Source: Google Maps

Across the 75-acre campus, the YOC houses residential dormitories — known as cottages — a juvenile detention center, juvenile court services, recreational fields and trails, offices and a school. Residents who are extremely below grade level or have safety risks are the only ones who make the three-minute walk from their cottages to the on-campus school. All other residents board buses to attend Muncie Community Schools.

Within the on-campus school setting, Williams said, the focused attention enables residents to catch up under the guidance of MCS teachers in a slower-paced environment.

But for one class period Monday and Wednesday or Tuesday and Thursday, 11 middle- to high-school-aged residents, selected by the YOC school’s director, have the opportunity to experience their first books and connect with relatable characters in the multipurpose room, filled with three rows of cafeteria-style tables used for lunch and after-school activities.

Waiting for them are 11 Ball State University students, or “Reading Buddies,” who spend an entire semester coaching the residents through two reading interventions. This year’s students make up the seventh group Ruth Jefferson, Ball State associate professor of special education, has trained for the program.

"I think this is an amazing opportunity for both our residents and the Ball State students because it's more like a supportive relationship," Williams said. "It's somebody showing up to help these kids, cheering them on and being in their corner. The Ball State students get to learn how to work with kids who are the most vulnerable, and they start to look at all kids differently."

CHAPTER 2: Showing they care

Most Ball State students start each session with their buddy by practicing sight words, spelling and reading fluency within a workbook. These activities are based on a resident’s level of reading, said Janay Sander, creator of the study and a Ball State associate professor of educational psychology.

After 20 minutes, the pairs switch to what’s called the Peer Assisted Learning Strategies (PALS) intervention. For this program, the residents read and pause when they run into words they don’t know so their Ball State partners can write them down. After five minutes, the Ball State students pick up reading where the residents leave off.

When the pair finishes reading, they go back and discuss the unknown words, using context clues to determine their meaning. The residents summarize the content from the reading in 10 words or fewer, often counting on their fingers to keep from going over.

“We chose these programs because we wanted to find out what you do with an adolescent who is significantly below grade level in literacy basic reading skills and how you catch them up,” said Sander, a licensed psychologist who started the program. “The SRA corrective reading intervention was originally designed as an adult literacy program. We wanted to see if it would be engaging enough for adolescents, and the answer to that is yes.

“Reading interventions like this are ‘tried and true.' They’ve been in the [research] a long time. They’re not new interventions, just the way we combined them is new, as well as the population and the setting. We were one of the few that’s done it with this population.”

Sander also said it was built into the interventions that everything had to be positive. The goal was to make sure mistakes were viewed as learning because that’s what they are.

Even though both interventions are scripted, the second one allows residents to choose what book they want to read, from chapter books and novels to Dr. Suess books. Although, Jefferson said, she and her students often make suggestions to residents if they think a book would be too easy or too hard for them.

If a resident wants a book that’s not on the shelves, Sander, Jefferson or one of the Ball State students retrieves the title from the Muncie Public Library. Sander said some residents are shocked anyone would go out of their way to fuel their interests.

Ball State immersive learning class and graduate assistants a part of the YOC reading intervention pose for a class photo March 27, 2018. Janay Sander, Photo Provided

Allison Dotson, junior elementary and special education major, was partnered with a ninth-grader who started at a first-grade reading level. Dotson said she has seen her reading buddy “grow immensely” because he recognizes more sight words and has better reading fluency.

Like Dotson, Megan Marchal, junior elementary and special education major, said she has seen the resident she works with come a “super long way since they started” as well.

“If you pick a book for a student, it’s kind of like you’re forcing it upon them, and some students already don’t want to read,” said Marchal, who joined the program because she wanted to work with elementary-aged children and thought it would teach her valuable skills for the future. “So, when they actually get to pick something they’re passionate about, they’re more likely to want to pick it up and read it. They get more excited about it, and the more they read, the more they learn, so being passionate about a book is definitely helping push them along.”

CHAPTER 3: Creating the program

In the past, Sander said, the YOC had a reading lab on campus, but over time, the facility didn’t have the resources to keep up with the priority. So, when she was interviewing for her position at Ball State in 2012, Sander knew she wanted to do juvenile justice research and saw the high priority for reading interventions at the YOC.

“Many kids who have court involvement end up dropping out of school and have fewer opportunities for employment because of that,” Sander said. “They also traditionally have below-grade-level reading skills, but if they learn to read, they can learn almost anything. It’s an essential life skill that once you have that door open to you, there are endless possibilities. So, I wanted to try to help them overcome those barriers.”

In 2012, Sander presented the center with a menu of research studies that would both support their residents and advance her field’s understanding of the importance of reading for juveniles. Officials at the YOC chose the combined reading study that has evolved into the program in place today.

“When Dr. Sander presented this opportunity, we were extremely excited,” Williams said. “It was kind of a missing piece of the puzzle … We knew that this program could really get our kids back on track educationally. It was a no-brainer.”

In January 2013, Sander applied for a grant from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ). Even though Ball State is a special niche school for obtaining partnership grants, this was the first application submitted through the university to the NIJ.

Sander spent roughly five months creating the proposal, but it wasn’t until she submitted in 2015 after three rounds of revisions that the program was accepted. The grant allotted $388,000, plus 40 percent indirect costs, and required the intervention last three years — two years for data collection and one year for follow-up.

Next, Sander began searching for a partner, and she heard from some of her students Jefferson was already trying to pilot a few interventions in Muncie Schools, so she decided to cold-call her. After their discussion about the details of the project, Jefferson agreed to join the effort.

“Dr. Jefferson’s expertise and passion really aligns with my expertise and passion,” Sander said. “It was definitely an alignment of values and passion in a shared vision for what the kids needed that kind of made the magic happen, which I don’t think is true for everyone’s project. I think that’s important though. If that value piece doesn’t align, it’s not always worth it.”

CHAPTER 4: Finding participants

Together, Sander and Jefferson outlined the three main questions of the reading intervention: Could they move residents up in reading skills? Would this improvement also help their emotional and behavioral functioning? Would the intervention help them be successful after they left the facility?

In January 2016, Sander and Jefferson recruited and trained the first group of students, which Sander said was a challenge because they had to find students who had openings in their schedules in the afternoon three days a week.

Two classes partnered for the project: Jefferson led a special education class to perform the intervention, and Sander guided a graduate class to compile and analyze the collected data. All of the participating Ball State students also had to go through background checks and drug screenings, which typically took six weeks.

At the same time, the pair worked with the YOC to begin testing residents who volunteered to join the program. Sander said five screening tests were used to determine a resident’s reading level and whether or not they thought, reasoned and remembered at a high enough level for the program to be effective. Residents who met the restrictions were split into two groups: a control group that was not given the intervention and an experimental group, which did participate in the intervention.

“Dr. Sander and her team didn’t really rely on us at all. They’re the ones who did most of the legwork as far as contacting parents and placing agencies to get permission to interact with the kids,” said Williams, who has worked with students in the juvenile system for 16 years. “But, there was a lot of coordinating with the schedule. We have to make their day very structured. That includes them having time for homework and counseling, as well as their own chores so they can maintain a nice and clean environment. So, we had to make sure they had time to participate in this reading study, and at first, that was hard.”

CHAPTER 5: Making an impact

Throughout the program, the residents took monthly reading tests to track their improvement. Halfway through the three-year project, Sander said, she and Jefferson felt “absolutely terrible” about having a control group.

“Some of the kids came every month and took reading assessments with us, but we didn’t provide them with the reading intervention,” Sander said. “We weren’t completely sure what the long-term outcomes were going to be, but we were like, ‘We know that these kids who are coming are getting better, and it feels horrible that these other kids will never have access to the same interventions again.’”

During the first year of the study, Sander said, there was one resident who came consistently until he left the YOC. Each resident typically stayed for roughly six months, and they each got to pick a book to take with them, but Sander and her team let this resident choose three because of his dedication.

When residents participated for more than one Ball State semester, Jefferson and Sander agreed there were times it was hard because they would get to know one Ball State student and then get upset when they had to be paired with someone new. Other times, Sander said, it was almost like another confidence booster for the residents because they got to be the expert and “teach” the Ball State students how to do the programs.

Mackenzie Smith, 2019 Ball State alumna, and Abby Jones, graduate student, were two Ball State students who stayed on the project for over a year. Both women were able to conduct the intervention as well as collect data.

For Smith, this was her first time working with kids who have behavioral issues or learning deficits. She said she enjoyed getting to see how much the students she worked with improved based on their test scores.

“The YOC has residents that don’t follow along with other typical kids their age in terms of the way they experience school, their peers, any of that,” Smith said. “I think it’s really important that we were able to take the time with these kids to show them they matter and that just because they’re in the juvenile system doesn’t mean we should give up on them or focus less energy on helping them. I just thought it was really neat how we were the ones trying so hard to give them the extra help they needed.”

Jones, who also got to work on both sides of the project, said she had the chance to work with a resident who already enjoyed reading, but she got to see his confidence increase, as well as his test scores. Jones also said she volunteered to go back to the YOC at a different time to help a resident whose schedule didn’t fit with the program.

CHAPTER 6: Relocating and rescheduling

In 2018, when the NIJ grant ended, the Ball State teachers and students, as well as those at the YOC, wanted to continue the reading intervention, even if there were no longer reading tests each month.

Williams said educational assistants at the YOC — direct care staff who help residents with academics — were originally trained to perform the intervention after Sander and Jefferson left, but Jefferson was asked to continue, and she decided to make service hours an option for her special education students.

The program has now been incorporated into residents’ school day two days a week. Cassandra Shipp, the school’s director, helps choose which residents participate with the help of the teachers. Students are selected based on their reading levels, and then they are asked if they want to join.

“If you are looking at residential or juvenile centers, just something that can be very isolating for a student at a time, programs like this can be very beneficial,” Shipp said. “This program specifically focuses on some of the gaps in residents’ reading, which can then transition over into other classes.”

Lindsay Price, YOC education coordinator, agreed the program has impacted other aspects of residents’ lives. As a whole, she said she has seen students improve in their science and math classes.

“Reading and comprehending what you’ve read are two very different things,” Price said. “Understanding what you’re reading is a game changer. It boosts a child’s confidence, which allows for more participation in class. As a result, we are seeing vast improvement in other subjects as well.”

The program also benefits the Ball State students involved, Jefferson said, because they are learning to work effectively with “a wide range of students.”

When they first designed the program, the goal for Sander and Jefferson was for anyone to be able to replicate it. Sander said schools in the country most likely already have the necessary textbooks sitting in a curriculum closet.

"We had several people at more than one conference come up after our presentations who maybe worked in a school similar to the YOC," Sander said. "They came up and wanted to know everything: where to get the material, how to get the training, how easy the program really was, etc. And I'm pretty sure they were going to go home and try to get a reading intervention started in their own schools."

The book cabinet may have closed on the research project, but everyone involved in the program hopes it will remain open for many more residents in the future.

"People don't really understand," Dotson said, "but kids in this population really do want to learn as much as teachers want them to. They want to succeed, and they want to make the people important to them proud."

Contact Tier Morrow with comments at tkmorrow@bsu.edu or on Twitter at @TierMorrow.