Sewage costs for Muncie residents might rise if the city’s current plan to separate sanitary waste and stormwater runs its course, according to the Muncie Board of Sanitary Commissioners.

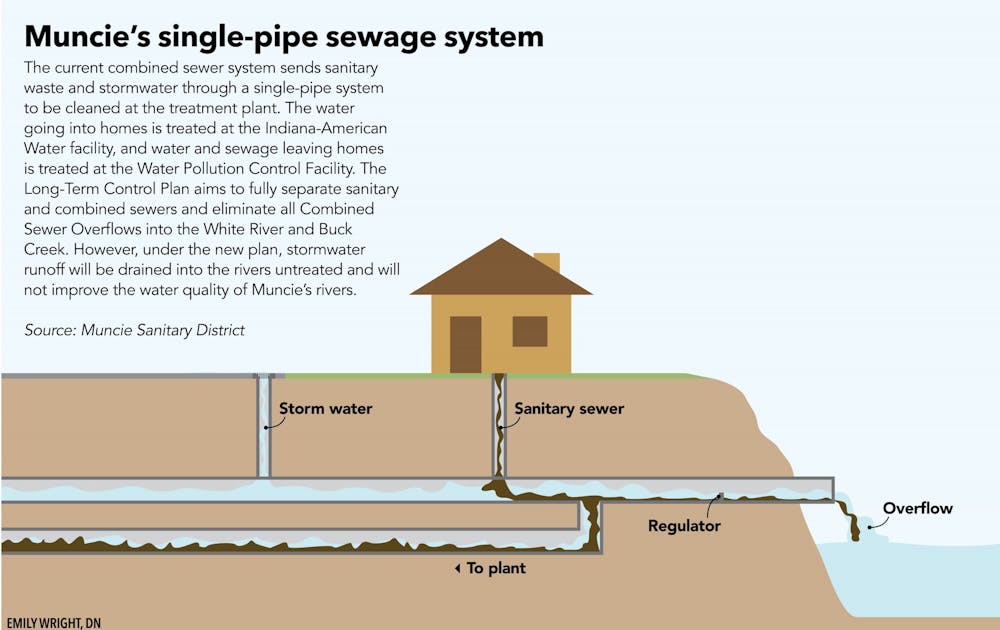

Muncie currently uses a combined sewer — where sanitary waste and stormwater travel through a single-pipe system to be cleaned at a wastewater treatment plant, according to Muncie Sanitary District’s (MSD) website.

Muncie has been using a single-pipe sewer system. Instead of switching to a fully separating sanitary waste and stormwater, Muncie Sanitary District is discussing a partial separation to reduct costs. Emily Wright, DN

During heavy rainfall, to prevent overloading of the treatment plant, excess wastewater flows out of Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs), the website states. There used to be 25 CSOs located along White River and Buck Creek in Muncie.

In 2011, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) approved MSD’s Long Term Control Plan (LTCP) to switch MSD’s collection system from a single pipe to separate sanitary and combined sewers, which would eliminate CSOs, according to the website.

The LTCP, which consisted of approximately 84 miles of sewers and a wet weather treatment facility at the city’s Water Pollution Control Facility (WPCF), was originally expected to cost $160 million. That number has swelled to approximately $200 million, according to a presentation given to MSD’s Citizens Advisory Committee meeting in February.

With this plan, approximately 100 homes in Muncie lose access to running water every month because homeowners can’t pay their bills, said William Smith, the board’s president. For those homes, he said, this means no access to water for drinking, showering or washing dishes.

Smith added the plan may cause the number of homes without water, as well as the average sewage rates — which is currently $40 per household — to double or even triple.

“It’s almost like a death penalty to somebody that’s economically in that situation,” he said. “After a certain point, it becomes economically not feasible to do a complete source separation.”

Muncie currently has 10 active CSOs, said John Barlow, superintendent at WPCF. As more work is completed on the project, he said, the cost estimates would increase due to both inflation and unexpected situations like unmarked gas lines.

“Once you start to dig, then you find all sorts of stuff that you didn’t anticipate,” Barlow said.

Instead of the LTCP, he said, the board is now looking to alter the plan to a partial separation of sanitary and combined sewers.

While a partial separation would allow for a minimum number of overflows, Barlow said, the original full separation plan would eliminate all overflows, meaning all stormwater runoff during heavy rainfall would eventually go into the river untreated.

“When we have runoff from rain events, I get a big portion of that here at the plant, which gets fully treated,” Barlow said. “Not 100 percent of it [gets treated], but a lot of it [does]. If you do full separation, that means 100 percent of storm runoff goes to the river untreated. That, in and of itself, has all sorts of constituents in it that aren’t good.”

Smith said MSD’s workers who test the river water quality on a weekly basis discovered that letting untreated stormwater into the rivers does not help keep them clean.

At this point in time, however, he said there is no mandate for the treatment of stormwater. Instead, MSD is hoping to gather more data to send to IDEM in an effort to prove the plan will not help improve water quality.

“Up to this point, [MSD has] been spending a lot of money to prove that this isn’t the best plan,” Smith said, adding that the sanitary district will need a lot of public support to get IDEM to listen.

Local business owner Kimberly Ferguson said this project would impact small businesses like hers that operate on a thin budget. As a landlord, she said an increase in costs will also make it difficult for her tenants.

“Many of the tenants that I care a whole lot about will have trouble with this — with being able to pay an additional $100 a month because they live paycheck to paycheck right now,” Ferguson said.

If nearly 100 homes get their water shut off now, Ferguson said, it’s reasonable to assume that number may also triple as rates increase.

“That’s going to be the poorest of our citizens,” she said. “That’s just not equitable, and it’s not fair.”

Ferguson said she doesn’t agree with spending this much money on a project, which she said was of little benefit to the community. She said she wants to get 5,000 like-minded community members to write to IDEM about changing the plan.

“If they don’t get more involved, it’s a done deal,” Ferguson said.

Contact Bailey Cline with comments at bacline@bsu.edu or on Twitter @BaileyCline.