Editor’s note: Dominic Bordenaro has previously written for The Daily News.

In her junior year of high school, she had rocks thrown at her at a bus stop by some students from her high school.

“The kids claimed it was because I was ugly,” said Brooklyn Arizmendi, president of Spectrum — the on-campus LGBTQ-resource organization, recalling the incident. “But I realized it was because I was brown. It was a very racist assault.”

But when she took the incident — which she said could have been prosecuted as a hate crime — to the person who handled disciplinary action at the Madison Consolidated High School in Madison, Indiana, Arizmendi said she was told to “to wait until it happens again.”

“I realize today that it was because those kids were extremely ignorant and racist,” she said.

On April 3, Gov. Eric Holcomb signed Senate Bill 198 (SB 198) into law, aiming to protect Hoosiers against hate crimes. But Arizmendi, like some state legislators and Ball State students, doesn’t fully support the legislation.

Indiana’s bias crimes reporting statute mentions color, creed, disability, national origin, race, religion and sexual orientation, but doesn’t explicitly cover age, sex or gender identity.

However, the newly-signed legislation says bias is also considered “due to the victim's or the group's real or perceived characteristic, trait, belief, practice, association or other attribute the court chooses to consider.”

Arizmendi said all protections for marginalized groups are important and it was necessary to be more specific on who is protected.

“I think that when they removed language protections for the majority of the LGBTQ+ community, it then becomes useless to us,” she said. “It doesn't serve the original purpose and it's very, very passive.”

Rep. Sue Errington (D-Muncie) said she supported SB 12 — which included age, sex and gender identity — because “it provided a complete list of characteristics that a judge could consider when deciding whether it was a hate crime and having the enhanced sentencing because of it.”

Instead of SB 12 the legislators ended up with SB 198 — which Errington said was a different bill in which hate crimes language was amended into on the floor of the house.

“It didn't even get a hearing and a committee where the public could come and testify pro and con,” Errington said. “I think we've got a partial [legislation] and I think it misses the most targeted people for bias.”

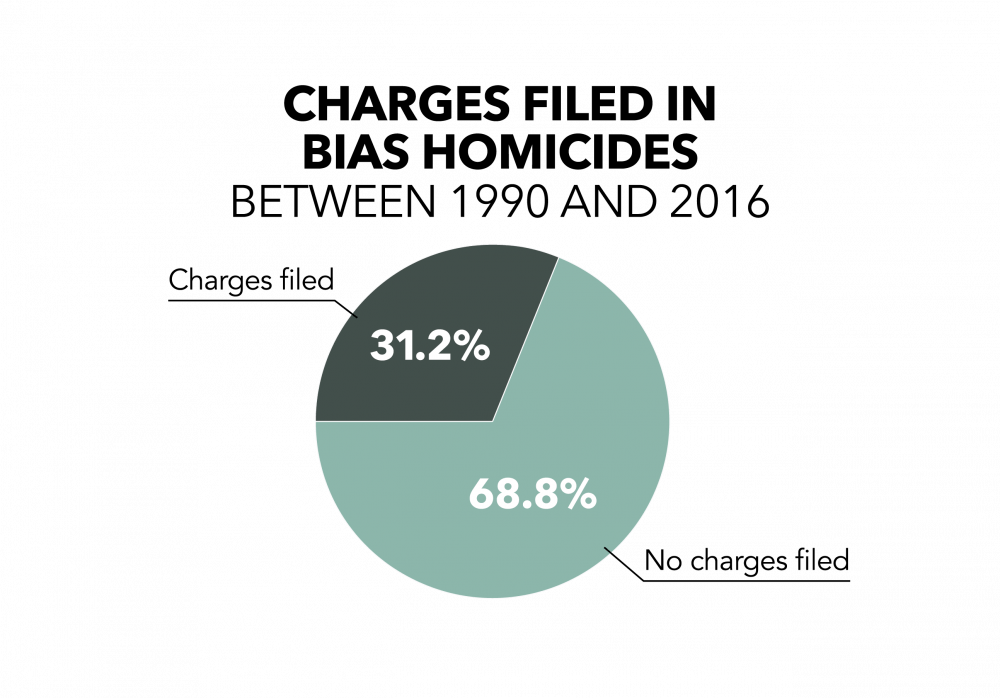

The Indiana University Public Policy Institute’s Center for Research on Inclusion and Social Policy’s analysis of 317 bias homicides, 567 offenders and 411 victims between 1990 and 2016 found “less than one-third of the bias homicides analyzed were charged as bias crimes, despite the indication that the victim was likely selected because of the victim’s social status or identity.”

Apart from suggesting that “legislation should include provisions for more detailed and regular data collection to allow for a more accurate evaluation of bias crimes,” the analysis also recommends prosecutors to “take steps to pursue bias crimes charges equitably to ensure equal statutory protection for victim groups and the equitable application of the law.”

Source: Indiana University Public Policy Institute’s Center for Research on Inclusion and Social Policy

Hate crime language in Ball State’s Annual Campus Security Report considers bias against the victim’s actual or perceived race, religion, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, national origin and disability. In 2016 and 2017 five hate crimes were reported on campus, according to the report.

Gaven Schulz, vice president of Ball State Republicans, was against the legislation for a different reason.

“When you're speculating why somebody committed the crime and then adding longer time to the sentence, that doesn't seem necessary, because at that point you're not punishing the person for the crime they actually committed,” Schulz said.

Without the legislation, he said judges still have the power to give longer sentences if they believe someone was hateful and it opens up the possibility of crimes that weren’t motivated by hate or bias being treated as such.

Schulz said while decreasing specific areas of crime is good, decreasing overall crime, which he said is already being done, is better.

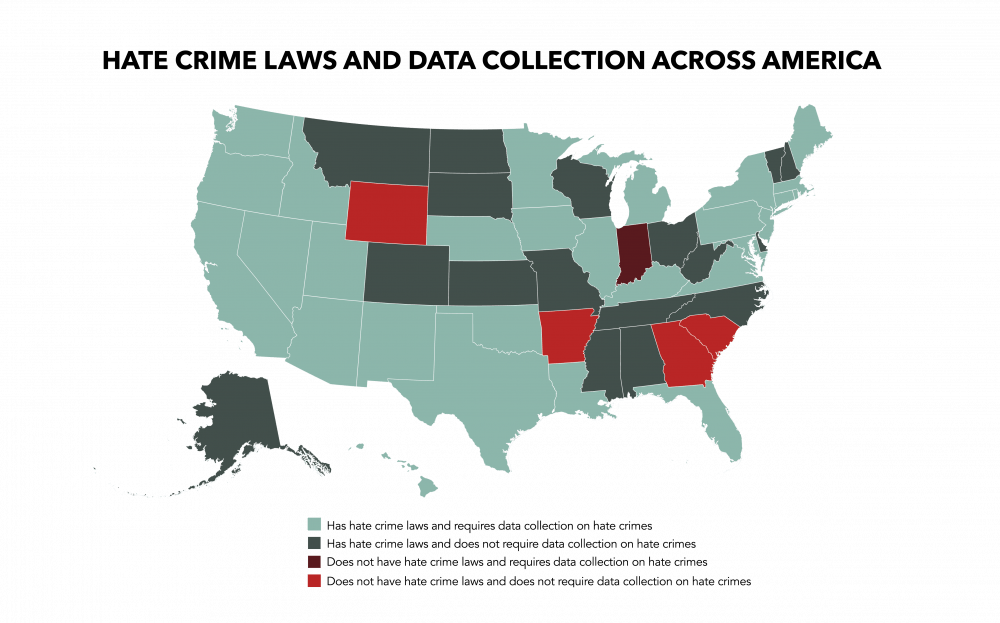

Dominic Bordenaro, president of Ball State Democrats, said the current legislation does not take Indiana off the list of states without hate crime legislation.

“[Holcomb] said he wanted the hate crimes legislation passed and [Indiana] taken off the list,” Bordenaro said. “And you can see that he failed. That’s very telling of the state party that has held onto power for so long.”

Bordenaro said Indiana has “shown a reluctance over and over again to protect our minority citizens — especially as related to the LGBT community.”

While he trusts investigators, police force and prosecutors to determine whether or not there is a hate crime before bringing charges, he said, there is “a huge problem with people being targeted” because of their skin color or sexual orientation.

“People will target you on the street because you’re gay. People don’t target you because you’re straight,” Bordenaro said. “Because of that there just needs to be harsher punishment for people who commit a crime based off of who you are.”

He said judges might hold biases and need to be given the guidelines to follow when it comes to punishing people for committing crimes against minorities.

Chad Kinsella, assistant professor of political science, said Democrats really want hate crime legislation to be “as broad as absolutely possible,” covering “all kinds of definitions” while Republicans had the idea that the crime committed “is hate in and of itself” which the judge and jury can take into account.

“The devil is in the details” — whether the law is inclusive enough or too vague, Kinsella said.

While it’s “a done deal now,” he said time will tell whether the legislation is strong enough or not when a case pops up.

“We're talking inches, not miles,” Kinsella said about the difference between the language used by the two parties. “But because it's a partisan issue those inches have to seem like miles.”

Matt Hinkleman, vice president of the Student Government Association (SGA) executive slate, authored a letter earlier this year to Indiana legislators asking to create a hate crime law in Indiana.

Hinkleman said he wasn’t sure why Republican lawmakers would pass legislation hurriedly “aside from just trying to get Indiana off the list of the five states without hate crime laws.”

He said the current law doesn’t really qualify as a “true hate crimes law” and is rather a “check mark.” He hopes the next SGA executive slate will draft a similar letter advocating for “more specificity in perhaps a new proposal” in the Statehouse.

“Well, I guess we'll have to wait and see,” Errington said about the current legislation’s effectiveness in deterring hate crimes in Indiana. “But in my opinion, hate crimes against, say transgender individuals; I would guess it's not going to deter that.”

Contact Rohith Rao with comments at rprao@bsu.edu or on Twitter @RaoReports.