Dodging book bags and benches, Preston Radtke dances his way through a crowded cafeteria on the way to his next class.

Navigating through the hundreds of students can be difficult considering the graduate student can’t see the various chair legs jutting out from precariously placed tables.

He very easily could brush up against an unsuspecting passerby or a stray tray, but he doesn’t thanks to a companion who stands no taller than his knee.

Preston Radtke walks up the stairs of the Ball Communications building on March 19 with his service dog Burton. Radtke uses a service dog for guidance because he is visually impaired, so Burton helps him navigate the space he is walking through. Rachel Ellis, DN

Radtke, who is visually impaired, relies on his service dog Burton to help him avoid everyday obstacles. The duo goes virtually everywhere together — something he said can be increasingly hard to do in a world where people are passing off regular pets or emotional support animal as service dogs.

“If it's just like a dog that you bought in the pet store and you're pushing it off as your own service dog, I think that really undermines the amount of training real service animals have to go through because it is a pretty intensive process,” Radtke said. “The dogs have to be the best of the best to actually make it through.”

Various experts such as Jennifer Cattet, 30-year service dog trainer and owner of Medical Mutts, say on average, service dogs go through a minimum of 120 hours of extensive skill training and 30 hours of training what it would be doing on a day to day basis in public. Because of the amount of training, there are only 10,000 service dogs in the U.S., according to Guide Dogs for the Blind, a service dog training facility.

Unlike emotional support animals that don’t require any training, Burton, who is now three, went through two years of training before finding his way to Radtke — a former cane user.

Larry Markle, director of disability services at Ball State, said a service dog must be specifically trained to perform a task or work for somebody with a disability. Additionally, service dogs are usually Labrador retrievers, golden retrievers, Lab/golden crosses and German shepherds.

What’s more, is that it can take up to five years for a person with a disability to obtain a service dog and can cost anywhere from $9,000 to $30,000, Catett said.

“It can be really hard to get a service dog for people who need them. So, when people pass their pets for service dogs, you know, it’s kind of the equivalent of parking your car in a parking space that is designated for a person with handicap,” Cattet, a service dog trainer, said. “Then the person who legitimately has a service dog and comes after that fake service is going to be questioned, they’re going to be looked at differently.

“They’re going to be concerned about them being there with their dog. And when you’re going to places and you’re constantly being questioned about your dog, it makes your day really, really difficult.”

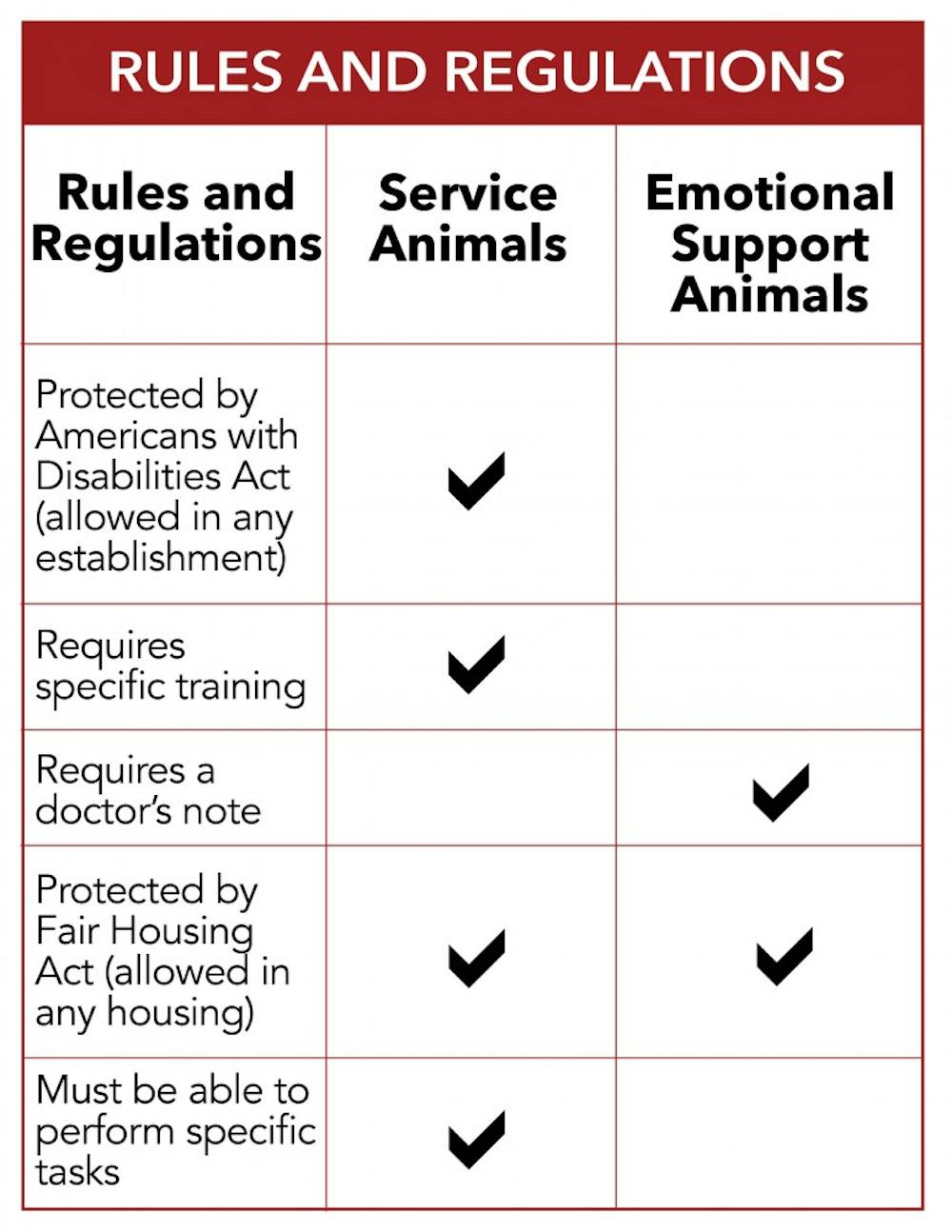

These rules and training, however, do not apply to emotional support animals, which can be another factor in the negative culture around service animals, Markle said.

According to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the only requirement for an emotional support animal — which can be any type of animal — is that the person who owns one must have a doctor’s note saying they have been diagnosed with a mental health disability such as anxiety or depression.

There are many different rules and regulations that separate the two animals. They include but are not limited to:

So, while emotional support animals aren’t allowed in certain establishments, service dogs are because of the tasks they have been trained to perform.

Burton, for example, began his training with a puppy raiser at 8 weeks old where he was taught basic skills any dog might learn. Then, he went to another trainer at The Seeing Eye, a facility that trains service dogs, who taught him specific tasks before he could finally be matched with Preston.

Puppy years

Anthony Knepp, who is best friends with and a roommate to Radtke, began raising a black Labrador puppy for Leader Dogs For The Blind after seeing the relationship between Radtke and Burton.

“[Burton] literally means so much to Preston, and somebody else had to have done what I'm doing now to get Burton to that point,” Knepp, a graduate student at Ball State, said. “It's just so interesting to watch. Preston by far does not need Burton, he's more than capable of navigating around without Burton, but it has definitely been very useful for Preston to have a dog. It's definitely made his life, in a lot of ways, a little easier to navigate.”

Anthony Knepp, graduate student at Ball State, takes Annley, his service dog in training, to Target to practice some commands on March 20. Knepp is teaching Annley commands like "left" and "right" as well as integrating her socially so she knows how to behave once she becomes a service dog. Rachel Ellis, DN

Knepp received his dog Annley in July and immediately began teaching her basic skills and socialization. Knepp said Leader Dogs For the Blind gives dogs to those in need for no cost, so he, as a puppy raiser, pays for nearly everything Annley needs out of pocket.

Annley will stay with Knepp until May, a few days shy of her first birthday. She then will go on to task-specific training and will finally test at the Leader Dog facility to see if she is ready to pass Leader Dog's program. If she doesn’t pass, however, Knepp said she wouldn’t be forced to work as a service animal.

“There's like a 50 percent fail rate, it's pretty high,” Knepp said. “But it's actually kind of cool, the 50 percent fail rate isn't necessarily because the dogs are bad or anything, it's actually just because the school is really mindful of what the dog wants.”

If a dog does not want to become a service dog, Leader Dog will place it with a police station, school, or back in the puppy raiser’s home. Knepp said if Annley were to fail, he would take her back in a heartbeat, but he really hopes she’ll pass and go to somebody in need.

“She’s just going to change somebody’s life,” Knepp said. “I sound so cheesy and so hokey, but I find it to be really exciting. I'll honestly be up so upset if she doesn't pass. I'd be happy to take her back and I love her and all that, but she's just so smart and she's just going to change somebody's world.”

After completing her year with Knepp, Annley will go on to work with a specific task trainer such as Danielle Abouhalkah, a Ball State graduate student.

Task training

Abouhalkah is on her fourth dog, a golden retriever named Corpus Christi, — Corpus for short — with New Horizons Service Dogs. She said her job is to teach the dogs task-specific functions that may differ depending on the type of person the dog will be paired with.

She is currently training Corpus for mobility and autism, meaning she will aid a wheelchair user or a child who has autism.

Service dog in training Corpus Christi throws away an envelope on March 20 at the Alumni Center. Graduate student Danielle Abouhalkah is a puppy raiser, and has been teaching Corpus how to open and close doors, fridges, and throw away paper. Rachel Ellis, DN

“So if I tell her blanket, she'll lay on top of me to provide deep pressure, and if you tell her to stop, like if someone yells at her to stop when we're walking, she should just fall flat on the ground,” Abouhalkah said. “That way, if a kid were to run away and they were tethered to her, then she prevents a kid from running.”

Abouhalkah, who also pays out of pocket to train Corpus, said she continues to do so because of the feeling she gets knowing a dog she had a hand in training graduates New Horizons and is paired with someone in need. Additionally, she said it provides her with an opportunity to teach the general public a little more about service dogs.

“The biggest misconception is that service dogs aren’t allowed in some establishments. So really, I would say a service dog can go anywhere a wheelchair can go,” Abouhalkah said. “Then I also say treat a service dog like you would treat a wheelchair. You wouldn't go up to a wheelchair and start petting it or be like, ‘Oh, you're so cute.’”

The new culture where people are trying to pass other animals as service dogs has made it harder for her to educate the public, Abouhalkah said. In fact, she had an experience a few months ago where a Buffalo Wild Wings employee wouldn’t allow her to bring Corpus in.

“We walked in and they're like, ‘Sorry, you can't bring your dog in here.’ So I said, ‘Well it's a service dog, so I can bring her in here.’ And they said, ‘Well, the last service dog we had in here was peeing on things and eating food off the table,’” she said. “So when you're taking a fake dog in places, it's a lot harder for the actual dogs.”

Service dogs are protected by ADA, which states the animals are allowed in any type of establishment. Emotional support animals are protected by the Fair Housing Act and the Air Carrier Access Act, which means they are always allowed in any type of housing situation, be it a dorm or apartment complex, but they are not allowed in restaurants or some businesses.

Service dog in training Corpus Christi pushes a filing cabinet door closed on March 20 at the Alumni Center. Graduate student Danielle Abouhalkah is a puppy raiser, and has been teaching Corpus how to open and close doors, fridges, and throw away paper. Rachel Ellis, DN

Abouhalkah said a good rule of thumb to telling the two apart is “four on the floor,” meaning a service dog should always keep all paws on the ground and stay focused on the task at hand. However, in today’s world, she said it is increasingly easier for people to get accessories that make their pet look like a service dog due to various websites like Amazon or Etsy.

“You can't just tell by the vest because so many people go on Etsy and they buy the cutest vest they can and then they walk into Walmart with their dog,” Abouhalkah said.

Markle, the director of disability services, said one way to tell if a dog is a service animal is by asking the handler the two questions ADA law allows:

1.) Is the dog a service animal required because of a disability?

2.) What work or task has the dog been trained to perform?

“One, a service animal has to be a dog. If somebody brings their cat in and says, ‘This is my service animal,’ it's not a service animal,” Markle said. “You can’t specifically ask for documentation, but if the animal is causing problems, if the animal is barking, lunging, having issues with bowel/bladder control then you have every right to ask the handler to remove the animal.”

The perfect match

After the dog goes through the necessary training and has passed a school's required tests — the ADA does not require service dogs to be certified — users such as Radtke and Carlos Taylor, Ball State adaptive computer technology specialist, travel to The Seeing Eye in New Jersey to be matched with a dog.

Upon arrival, Taylor said he underwent what is called a juno walk where a trainer holds a harness at dog height and walked beside him to get a feel for what gait and strength he would need from a dog.

Adaptive Computer Technology Specialist Carlos Taylor works on his computer on March 16 in Robert Bell. Ewok, his service dog, is trained to help Taylor around the office and at home because he is visually impaired. Rachel Ellis, DN

After a few more juno walks, the trainers chose Ewok, a German shepherd, for Taylor and they went through a two-week training course before heading home. Radtke, who was a first-time dog user, stayed four weeks to get acclimated.

“It's like learning an entirely new skill, because if you use a cane, you’re just relying on yourself, but if you use a dog, you have to learn to trust this being that you were just introduced to,” Radtke said.

Once at home, it was up to Radtke to continue Burton’s training.

“They aren't perfect and neither are we as the handlers, like, both of us exit will make mistakes,” Radtke said. “So let’s say I’m walking, and he brushes me up against a tree — yes, that is his fault, but I don’t want people to think he sucks at his job just because he made a mistake.”

In an instance like this, Radtke said he would take Burton back to the spot where he made a mistake and they would do the task over until he gets it right. While it has been an adjustment, Radtke said having Burton has many benefits, the best of which don’t involve navigation.

“He’s very perceptive of my feelings. He’s a very good guide dog, he does the navigating just fine, but he’s very in tune with how I feel a lot of the time,” Radtke said. “If I’m in a good mood, then he’s usually in a good mood. If I’m sad, then he really tries to cheer me up and it’s just kind of relieving, or refreshing to kind of have such a bond with another living thing that understands me that much.”

Michelle Kaufman contributed to this story.

Editor's note: additional information about service animal training was added to this story after publication.

Contact Brynn Mechem with comments at bamechem@bsu.edu or on Twitter at @BrynnMechem.