Ball State pitching stats

Innings pitched - 358.0 (1st MAC)

ERA - 3.95 (2nd MAC)

Strikeouts - 291 (3rd MAC)

Strikeouts per nine innings - 7.32 (2nd MAC)

Walks - 154 (3rd MAC)

Walks per nine innings - 3.87 (2nd MAC)

*Editor's note: After being interviewed for the article, Zach Plesac was pulled after throwing 40 pitches in two innings against Bowling Green State University on April 23. After the game, head coach Rich Maloney said Plesac “wasn’t feeling right” and they didn't want to take any chances with injuries. At practice April 27, Maloney didn’t disclose an injury, but said Plesac is “on the D.L.” for now.

Pitch counts have become synonymous with arm injures in recent years, but today’s crop of collegiate pitchers are the first to come through a youth system with built-in limits.

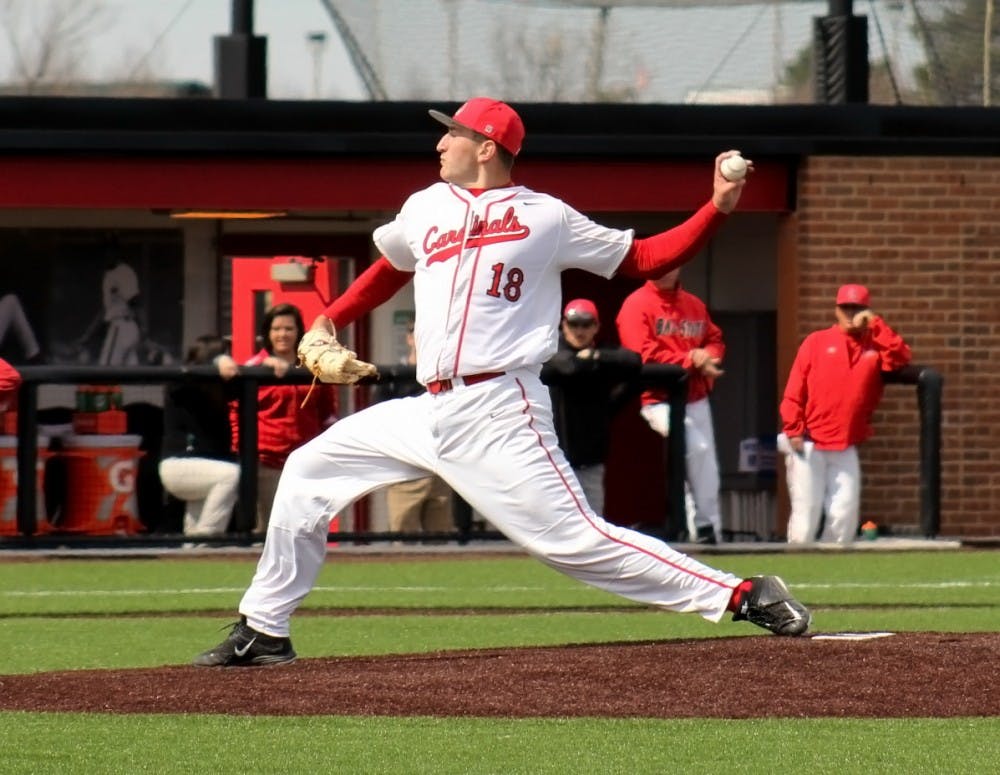

Zach Plesac, a junior right-handed pitcher for Ball State, said he was 11 when Little League International first implemented maximum pitch counts and mandatory rest between outings in 2008.

“It was right at that point where they started restricting the pitch counts and making sure people are on the right pitching limits,” he said. “I think it was a good thing ... starting that effort at that young age because it prevents them from being overused when their body feels great. … When you’re that young, you’re always feeling great.”

Ball State pitching coach Chris Fetter, however, said pitch counts do not guarantee a clean bill of health.

“You have to take anything that people say about pitch counts with a grain of salt,” he said.

There’s no magic number of pitches that will keep a player safe, he said. At Ball State, pitchers are generally limited to 85 or 90 pitches early in the season, gradually increasing their pitch counts throughout the season. Fetter, who played minor league baseball in the San Diego Padres system and was an assistant pitching coach with the San Antonio Missions (AA) in 2013, said the Cardinals’ maximum pitch count is 120, but pitchers rarely reach that total.

“Once you get past 120, that’s when you start to redline it a bit, [but] we just play it by the guys,” he said. “There are some innings and some pitches that are just more stressful than others. So say if a guy has thrown a couple of 30-pitch innings, his threshold isn’t 120. We have to monitor him because he’s been under some stress.”

Still, Fetter said staying healthy is more than just limiting the number of pitches.

“Everything kind of factors in,” he said. “There’s an ease of operation when you’re on the mound. The guys that can repeat, the guys that have stamina, the guys that have the strength — they ultimately do it a little more easily and, in turn, don’t get hurt as readily as the others do.”

Plesac said effective pitching is the first part of staying healthy. Simply put, better pitches mean shorter innings. He also said proper form is important because using the entire body limits stress on certain body parts, like the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in the elbow.

“I think mechanics play a huge role,” Plesac said. “You know, making sure your body is connecting at the right time to make sure you put the least amount of stress on your arm as you can. When your body’s disconnected or you’re throwing out of position, it just puts more pressure on your arm.”

Tired pitchers can often revert to bad habits that increase the risk of injury. Plesac said that’s why the Cardinals emphasize a strong running program.

“When you’re in shape, that keeps your body strong enough to make sure you’re in the right position when you’re going down the mound, especially late in the game,” he said. “When you start getting tired or you’re not strong enough, you start not being consistent with your body. … Next thing you know, you’re stressing your shoulder too much.”

Ball State pitchers also throw every day, though not necessarily on the mound. Fetter is a proponent of throwing long-toss to build arm strength. Younger pitchers, he said, sometimes have difficulty adjusting to the daily program at Ball State. In the summer, they usually pitch in weekend tournaments then avoid throwing until the next weekend's tournament.

“Their idea of rest and recuperation is to just not throw,” he said. “No, that’s not really helping yourself. You’re just setting yourself back. It’s kind of like if you were to lift only once a week — every time you lift you’re gonna be sore, as opposed to the guys that lift three to four times a week. You get rid of that soreness and get adjusted to it.”

Though several studies, including some by Dr. James Andrews, a surgeon famous for working with professional athletes, support pitch counts as a way to limit injuries, Fetter said it is still dependent on the individual pitchers, their conditioning and their mechanics.

“There’s no exact science, but we just try and do the best that we can given the information that we have to protect our guys,” Fetter said. “We don’t want any injuries on our hands.”