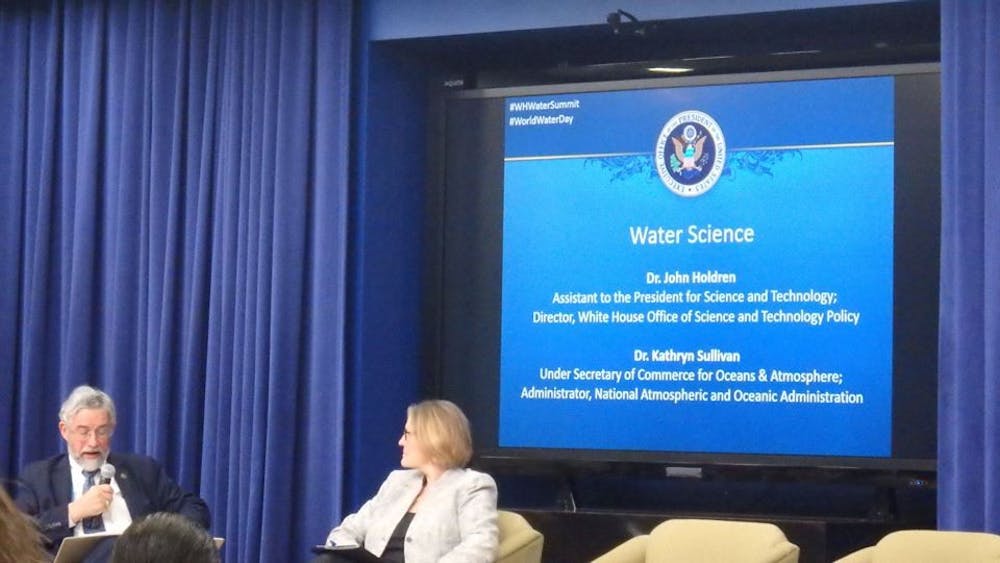

Lee Florea represented Water Quality Indiana at the White House Water Summit in Washington, D.C., on March 22.

Florea, an assistant professor of geology, said high-profile water issues, like California’s drought and the Flint, Mich., water crisis, played a role in the summit’s creation.

“Like they said, this is our most treasured resource,” he said. “You cannot live without water, you need water, and we take it for granted so often.”

Water Quality Indiana was created by Florea and Adam Kuban, an assistant professor of journalism at Ball State. The program was first available to students in 2013, but they said the idea came together in Fall 2011.

Kuban said national issues have brought water quality to the forefront of the news.

“It’s unfortunate, but an issue like Flint that gets national exposure definitely puts water quality in more of a spotlight than in recent memory,” Kuban said. “But it’s always been there. Even if it’s been on the back burner, so to speak, in terms of priorities.”

Students who participate in Water Quality Indiana measure water quality in Hoosier rivers, including Muncie’s White River. They then make news-style videos to present the findings and other issues with water quality.

Though Indiana is not in a drought and the water quality issues aren’t as severe as Flint, Kuban said keeping an eye on local waters is pretty much the point of the program.

“We look at hyper-local issues that might contribute — perhaps adversely, maybe not — but we suspect that there might be some adverse impact from hyper-local water quality issues,” he said.

Kuban said the students learn just as much from their peers as they do from the instructors.

“When you look at it, it’s a big spider web of knowledge shared and knowledge gained,” he said. “I think that’s exactly what higher education should embody.”

The stories of discolored water in places like Flint, he said, were likely a result of rusty pipes rather than lead. But it isn’t just lead — nitrates and other chemicals can affect the water supply.

“There are lots of things that are in the water that may not necessarily be visible,” he said. “For example, with the Flint thing, you can’t see lead in the water.”

Blue-green algae, for example, can grow in waters with high nitrate and phosphorous levels. Two major problems created by blue-green algae are oxygen depletion when the algae dies — effectively suffocating nearby fish — and toxic chemicals released by certain strains of the algae.

“A low concentration’s not a big deal,” Florea said. “But if you get high concentrations it can be a bit of a neurotoxin. It can cause weird reactions and skin reactions and also neurological reactions.”

Kuban said Florea's scientific background is why he couldn’t fault the decision to have Florea participate in the White House Summit instead of him.

“When [the summit organizers] looked at my credentials and [Florea’s], they decided they wanted the hydro-geologist more than the journalist,” he said. “Water is in his title; that makes more sense to me.”

Because of their different backgrounds and professional needs, Kuban said he and Florea butted heads a little at first as they tried to figure out how to run the program. Over time, however, he said they fostered an excellent relationship that keeps the program running smooth.

Florea said teaching diverse group of students in the program to develop similar professional relationships is just as important as being recognized at the White House, if not more so.

“If they have at least some context of how to work together with people of different opinions and different backgrounds to solve a common problem, then I think we’ve done our job,” he said.