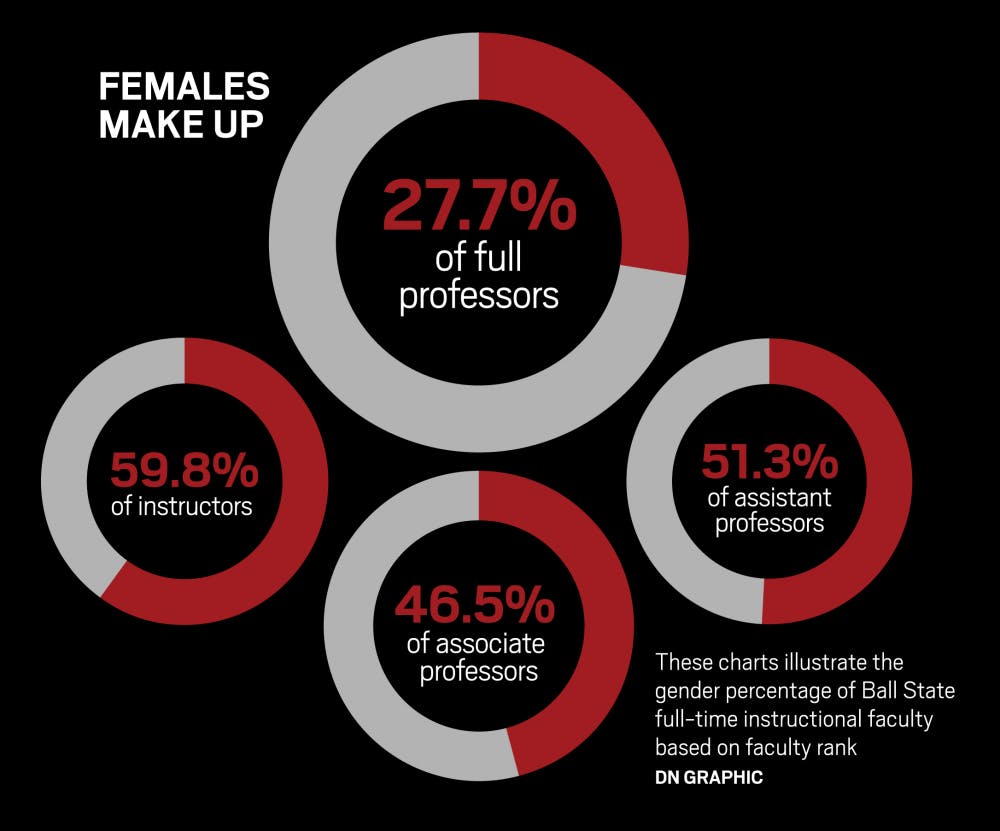

Although Ball State faculty is split fairly evenly along gender lines, there is one level where women are vastly underrepresented — full professorship.

Women currently make up just 27.7 percent of professors at the full professorship level, which is a tenured professor who usually serves at leadership positions within departments. That number has maintained relatively steady over the past five years.

It’s not just female professor leadership that is lacking at Ball State — currently, there are no women at the university in the top 10 salary earners, and there are only four in the top 20, according to salary data from the university.

However, more than half of the president's committee is female.

In order to become a full professor, a person needs to pass a review conducted by renowned professors and colleagues from across the nation that assesses three academic areas: research, course load and leadership in the form of seats on academic councils or boards.

The process usually takes a minimum of 14 years to complete but comes with a hefty boost in pay and reputation.

Full professors, on average, make more than double that of entry-level professors and a little more than $20,000 more than associate professors, the level below full professors.

Ball State is an equal opportunity employer and always looks to hire the best person for the job, Joan Todd, a university spokesperson, said in an email statement. She pointed to the university’s Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action policy that says, in part, “...the University is committed to the pursuit of excellence by prohibiting discrimination and being inclusive of individuals without regard to race, religion, color, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression, disability, genetic information, ethnicity, national origin or ancestry, age, or protected veteran status.”

RESEARCH COMMITMENT

While female professors usually teach the same number of courses and serve on the same number of boards as their male counterparts, they often struggle to conduct enough research to fulfill the strict requirements, either because they are often expected to do more work with their family or simply because they were outright dissuaded from pursuing a career in research, said Anne Runyon, chair of the National American Association of University Professors’ committee on the status of women in the academic profession.

She said a combination of these two factors has traditionally kept women from succeeding in bids or even considering applying for full professorship.

“I think it has to do with a prevailing underlying gender assumption that women are more teachers,” she said. “They are not [thought of as] researchers, even though they may have very similar credentials, and they are not taken as seriously.”

FAMILY RESPONSIBILITIES

Another issue is that of timing. Around the same time as a professor would be considering whether to continue in academia and seek full professorship, they are considering starting a family.

For female professors, this often means taking leave for pregnancy, which, because women are often expected to focus more on a family, means less time for teaching and research.

“With long hours spent in labs, it is very difficult to combine that kind of work with family responsibilities,” Runyon said. “Women tend to jump to private entities [instead].”

Carolyn Kapinus, associate dean of Ball State’s graduate school and a professor of sociology, said Ball State falls into the trap of expecting female professors to choose between familial responsibilities and research.

An easy solution universities could employ is providing on-campus child care for professors so they can work on research and stay on campus longer while still being close to their children, she said.

Ball State does offer professors access to the nationally accredited Child Study Center that offers child care for some infants and toddlers on campus and gives students in the family and consumer sciences department a chance at hands-on learning.

LEADERSHIP REQUIREMENTS

Another hindrance to research for female professors is university committees often require a certain number of members for academic boards to be women or people of color, Runyon said. Because there are so few female full professors available, many have to pull double or triple duty, serving on several boards to fulfil the diversity requirement.

A way to alleviate the time commitments pressed on female professors while still ensuring women are represented on executive boards is to promote inter-college collaboration in research, Kapinus said. That would allow professors to work and publish research while sharing the workload and freeing up time to serve on boards or take care of family responsibilities.

Runyon said universities should also work to build an environment that allows flexible work hours that allow for time spent with family while still requiring the same rigorous requirements for full professorship. Another is to acknowledge female professors often are expected to serve more time on boards and to take that into consideration when evaluating candidates.

“As you move up the ranks, more time is expected for research, and if the [diversity] requirements don’t change — if they have to keep representing women — [women] simply won’t have the chance to pursue [full professorship],” Runyon said.

The bigger problem, though, is that there simply aren’t many models for female professors to follow as a path to full professorship.

At Ball State, new professors are paired with a mentor to ensure they find a fit at the university. Kapinus contends that informal mentoring process should continue as professors reach the midpoint of their career and need someone to look to as a model.

The situation does look as if it’s starting to change, though.

In the next five to 10 years as the United States economy continues to recover, Kapinus expects a wave of retirements across higher education, which means there will be spots for women graduating with Ph.D.s to fill.

“That means new hires, and we need to make sure to have the best type of people,” Kapinus said. “Universities need to be mindful of the barriers in place to ensure that.”