Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported that Haruka Nakamura is half Ainu and her grandfather was full Ainu. Nakamura said that is not the case. The article also said that the Ainu people lived in houses called kotans. Kotan is the name for the village communities Ainu people lived in. The Daily News apologizes for these errors.

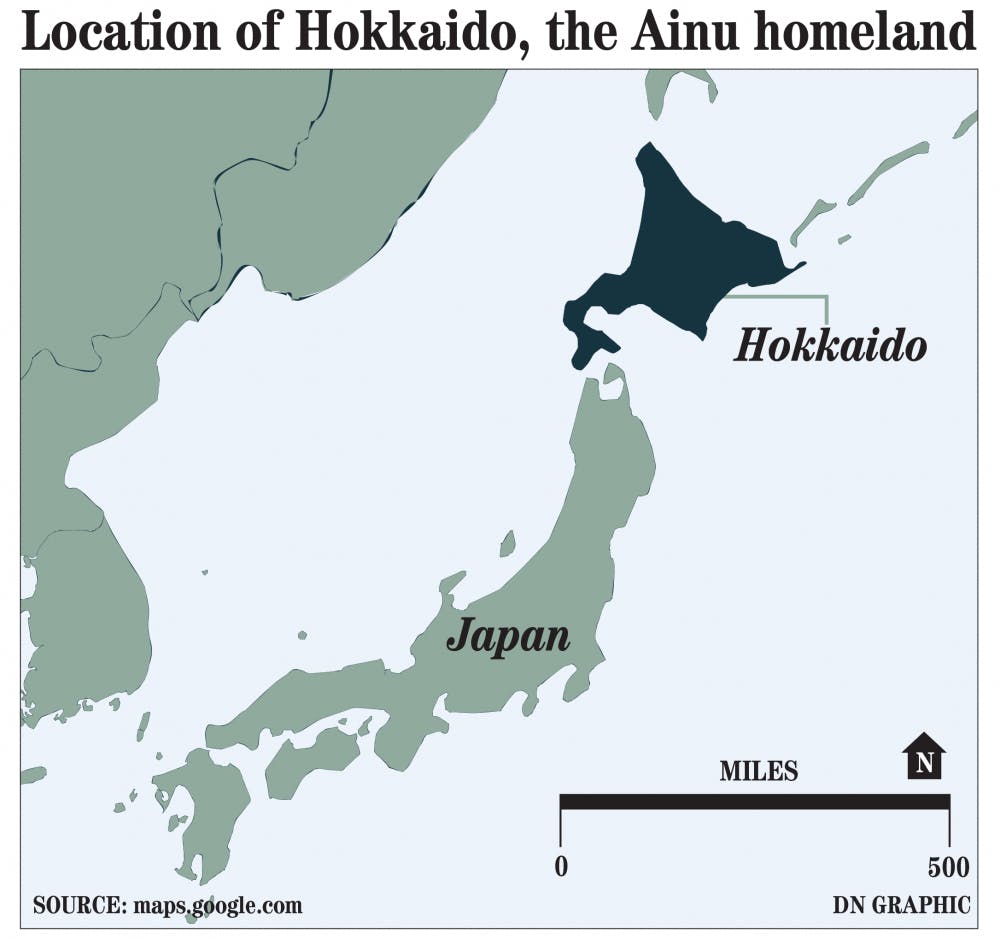

Japan is sometimes seen as an ethnically homogenous nation, but in 2008, the Japanese government recognized a separate group of indigenous people: The Ainu, who live primarily on the northern island of Hokkaido.

Haruka Nakamura, a student at Ball State’s Intensive English Institute, is Ainu, and she's made it her mission to educate others about the group. She was born and raised on Hokkaido, where her family still lives today. Being Ainu has long been a part of her identity even though she is not fully Ainu.

“When I was in elementary school, my mother told me, ‘You are Ainu,’” Nakamura said. “It is just something I have always known.”

The Ainu had their own culture before being colonized by the Japanese in the late nineteenth century. They relied on fishing and hunting for food, they lived in communities called kotans and their religion was earth-based. The Ainu prayed to various nature, animal and plant gods in daily ceremonies, according to the website for the Ainu Museum.

“In Ainu culture, everything is [considered] god,” Nakamura said. “Ainu didn’t waste anything, because everything living was [considered] god.”

The Ainu homeland Hokkaido was a target for early Japanese colonization.

Policies put in place on Hokkaido were similar to those used in Korea and Taiwan, both of which would eventually be colonized by Japan. The Ainu were encouraged to assimilate into Japanese culture. This meant learning a new language and adopting Japanese names, said Elizabeth Lawrence, a professor of East Asia at Ball State.

Today, the Ainu population is very small compared to the overall Japanese population—even in Hokkaido. Lawrence said Hokkaido has more self-identifying Ainu than other Japanese islands.

“There are undoubtedly some negative stereotypes held toward Ainu people by Japanese, partly due to the fact that the Ainu represent a less advantaged social group,” Lawrence said.

More Ainu received welfare benefits than people who were not Ainu, and less than half of Ainu people graduated from college, according to a study done by the Hokkaido prefectural government in 2006.

Nakamura said some people don’t want to say they are Ainu. Her older sister “doesn’t care,” and never studied a lot of Ainu culture. Her mother has been discriminated against because of her ethnic background, Nakamura said.

As a student in Japan, Nakamura received a scholarship for being Ainu. It was at school where she first began studying Ainu culture. She has not met many Japanese students who know about the culture either.

“It was kind of sad for me,” Nakamura said.

Ai Shikano, a junior athletic training major at Ball State, is a Japanese student from Nagoya, a city on Japan’s main island. She is not descended from the Ainu people. At Ball State, she helps international and exchange students adjust to life in America. That’s how she met Nakamura.

Shikano was aware of the Ainu before she met Nakamura. The Ainu are well known, she said. She compared them to the Native Americans.

“Everyone is supposed to know [at least] about the meaning of the word Ainu through classes in school,” Shikano said.

During high school, Shikano went on a field trip to Hokkaido. She went to the culture center there, where she listened to lectures on Ainu culture and watched traditional dances. She wouldn’t say this is everyone’s experience, though.

“It’s because Hokkaido is not the main island,” she said. “People on the main island don’t usually have the opportunity to meet Ainu people, unless they go to Hokkaido or Ainu people come to the main island.”

Shikano said she and other Japanese students had not met many, if any, Ainu people before they met Nakamura.

“From the first day, [Nakamura] was saying she was from Hokkaido and Ainu,” said Shikano. “She talks a lot about being Ainu. It’s one of her purposes in the United States—to present the Ainu culture.”

Nakamura is a member of Urespa, an organization at Sapporo Universty, her university in Japan. Urespa consists of both Ainu and Japanese students. They learn about and inform others about the Ainu, she said.

“It is important for me to share my culture,” Nakamura said in a previous interview with the Daily News. “A lot of American people don’t know about Ainu, and even not many Japanese know about Ainu. I want everyone to know [about] Ainu.”