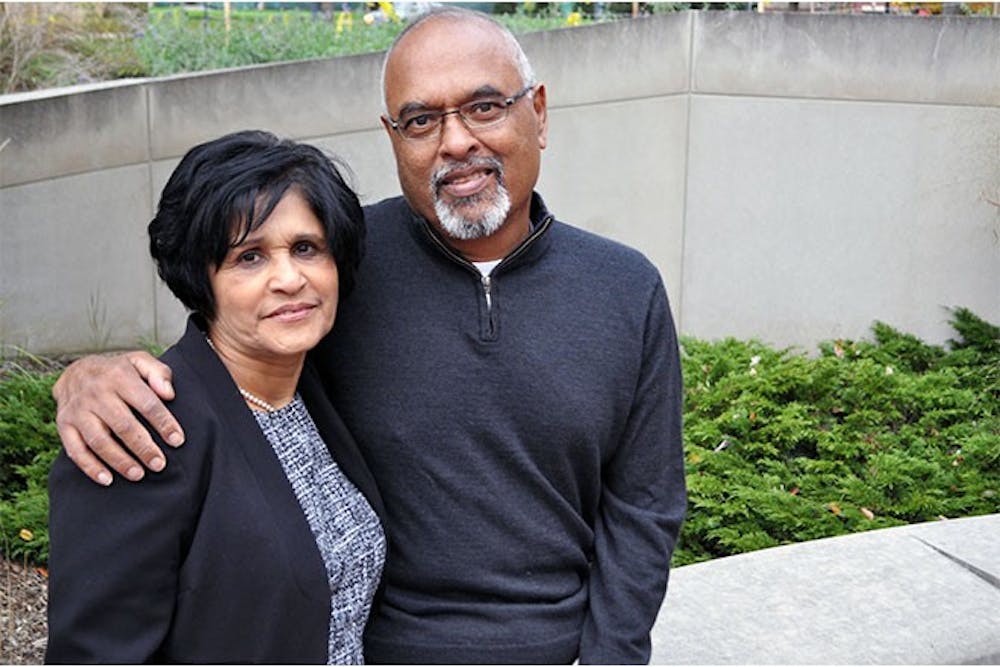

Husband. Father. Grandfather. Professor. Diabetic. All these words describe Srinivasan Sundaram, a Ball State finance professor, who has been diabetic for 33 years. In his first semester teaching at Ball State in 1991, he had a triple bypass, an open-heart surgery in which blood vessels are taken from one part of a person’s body and transferred to heart vessels to prevent blockage.

Sundaram, who suffered kidney failure, underwent dialysis treatments, which are typically over three hour treatments, three days a week. Dialysis treatment can destroy a person’s veins, which makes the procedure more difficult. He would sometimes go in for treatment, but would be sent home because the medics could not access his veins.

Along with treatment, Sundaram faced many dietary restrictions. According to the National Kidney Foundation, patients on dialysis need to eat more high-protein foods, fewer high-salt, high-potassium, high-phosphorus foods and learn how much fluid they can safely drink.

“End stage kidney disease can be very isolating since dialysis and transplants are the only treatment options,” said Janine Moore, the development director of NFK Indiana. “The most common form of dialysis, in-center dialysis, must be performed three times a week for three to five hours per treatment—that’s a part-time job.”

This leaves people like Sundaram, who work and do dialysis, with little opportunity for travel and hobbies.

Three years ago, Sundaram realized he would need a kidney transplant. He was put on two waiting lists: the cadaver list and the diseased donor list. On the cadaver list, Sundaram could receive a kidney from a deceased donor. On the diseased donor list, he could receive a kidney from a person with other medical complications, such as an HIV patient.

According to the Living Kidney Donor Network, there are over 80,000 people on the kidney transplant waiting list. Every year, 4,500 people die, waiting to receive a kidney.

To delve into the moral side of receiving a donated organ, read more at BallBearingsMag.com