Ball State’s stalemated geothermal project has been approved to receive $30 million despite generally dwindling state funding for higher education.

Muncie Mayor Dennis Tyler said approving the state budget was an easy decision for the Indiana lawmakers because of what the project means for the state.

“Evidentlly the general assembly saw the worth of this geothermal project for Ball State and my guess is the footprint or trademark that the geothermal project will have recognizing Indiana on the cutting edge of new technology,” he said. “By the state doing that, this is going to tremendously speed up on the process of the project.”

The state will fund the project in cash. Lowe said using cash means the project will only need to go through a couple steps of approval before starting.

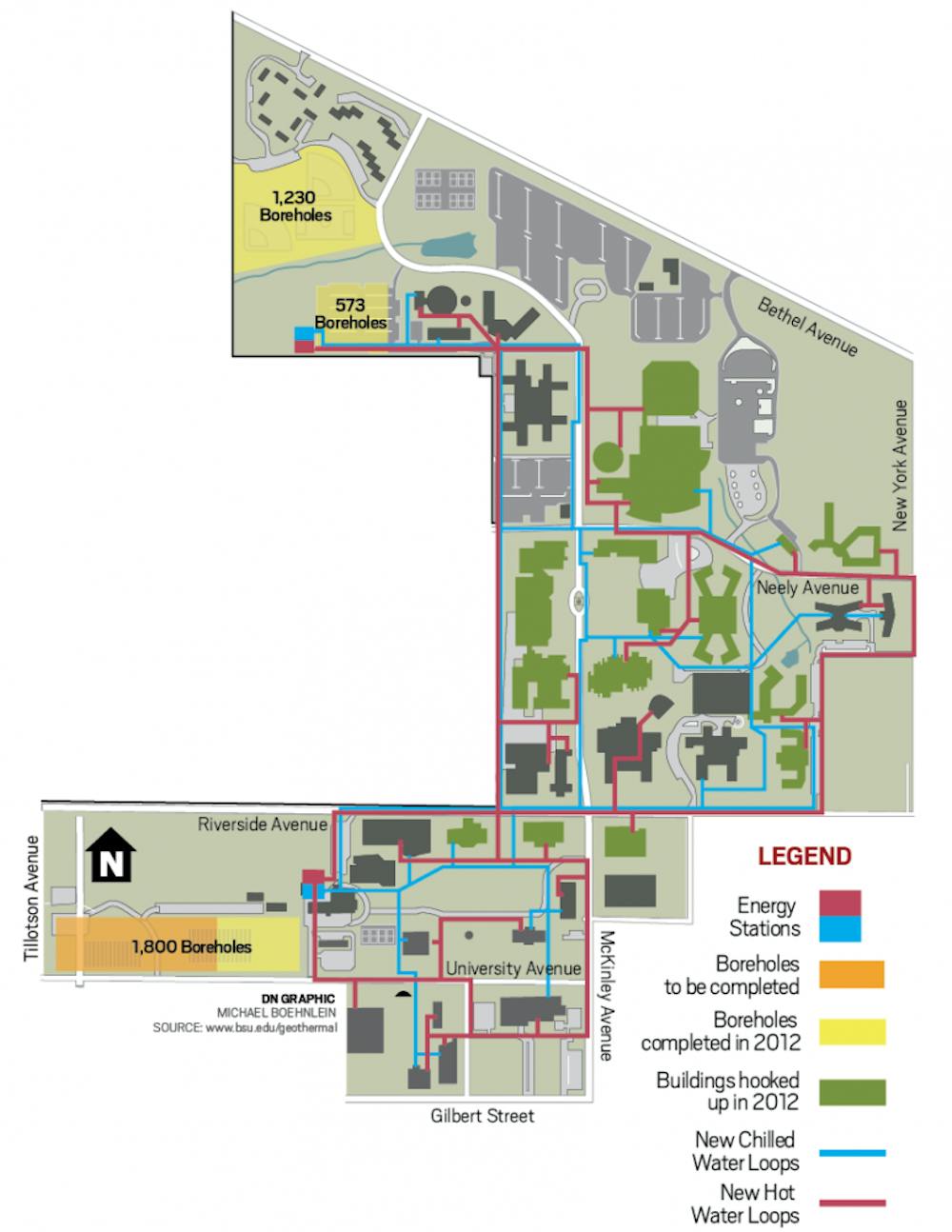

The last portion of the project on the south side of campus ended after funding ran out before all 1,800 boreholes were drilled. Lowe said drilling the remaining boreholes is just one of a few of his priorities.

“One of my first priorities is converting our old chill plant, to demo it to the degree that I can rebuild it in a fashion that’s very similar to the north station,” he said. “When done we’ll have almost two identical buildings, two identical operations.”

Lack of funding caused Ball State to miss their goal date of converting the entire campus to geothermal heating and cooling. March 2014 was supposed to be the date because the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will enact the Boiler MACT (maximum achievable control technology) requirement, which is pushing Ball State to reduce its carbon dioxide emissions.

The geothermal facilities will replace the World War I vintage generation facility, which emits roughly 85,000 tons of carbon dioxide annually, according to the Center for Business and Economic Research’s report on Economic Impacts of a Geothermal Replacement Plant at Ball State. ,

The new facilities will reduce the carbon dioxide emissions, while saving $2 million in generation costs and producing $1 million in electric power. The entire project will produce an estimated 487 construction jobs with an average annual salary of $39,000, according to the report.

“The situation is that since we’ve been patiently waiting for the opportunity of funding, we will miss that date for 100 percent completion of geothermal,” Lowe said. “My administrative plan is to shut down coal and burn more natural gas until which time we’re converted over to 100 percent geothermal and we’ll reduce out burn on natural gas.”

While Ball State is looking forward to leading the way in geothermal technology, other schools have had similar technology for decades.

Oregon Institute of Technology has had a similar geothermal system, or heating pump, since the ‘60s. Toni Boyd, senior engineer at OIT, said they’ve been benefiting financially.

“We have 192-degree water and we’ve heated our whole entire campus since 1960,” Boyd said. “We’re saving about $1 million in heating costs a year.”

The system at OIT is different in that it doesn’t cool the campus, and the water used to heat the campus is much warmer without electric generation needed.

Boyd said while they benefit annually from the heat pump, they have nothing physically to show for it, and neither will Ball State.

“Unfortunately, after everything is said and done, nobody is going to see it,” he said. “Nobody really sees geothermal, not like they see wind and solar.”

The geothermal facilities used to produce electricity are only applicable in areas where the ground has enough heat to produce steam and is usually found on the west coast.

“If you go 10 or 15 feet underground it’s hot enough to use that for heating an direct use applications but when you’re generating electricity, you have to be at certain locations in the U.S.,” he said. “You need to be in geological areas that heat the water and then that water can be steam or can be separated with a heat exchanger to generate electricity with liquid with a lower boiling point.”

Geothermal Energy Association Industry Analyst Ben Matek said about four million people in the U.S. use electricity produced by geothermal means.

“California is the biggest use of it,” he said. “They have about 2,700 megawatts, or about three million people in California get their energy from geothermal.”

Geothermal heating and cooling is the most common type of geo technology. When phase two is completed, Ball State’s will be the largest geothermal facility of its kind in the U.S.

Just as the previous phase took years of digging and drilling, the latest phase will require the same. Lowe said he is glad that there is a new beginning in sight.

“We just want to get these things started as quickly as possible,” Lowe said. “I’m hopeful that come September or October, assuming we can move forward with that approval, we’re restarting. It’s more likely that we’ll be done going into the winter of 2015-2016.”