In space, no one can hear you quote Charles Dickens, so forgive a tired but apt reference: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” The 54-year history of space exploration since Sputnik has had chapters that were thrilling, tragic, disappointing, and inspiring. The one now beginning may be the most frustratingly paradoxical, however.

On the one hand is amazing activity. Companies like SpaceX and Virgin Galactic are creating commercial space programs to pursue tourism, satellite launches and other opportunities beyond Earth’s atmosphere. China, a country that was once a bystander in the space race, plans to put human beings back on the moon. The Kepler space telescope has identified what may be more than 2,500 planets around other stars, and scarcely a week seems to go by without more discoveries being made about them.

Yet on the other hand, scientific exploration that involves actually going to other planets and deep space is more troubled. The U.S. manned space program is in shambles, and budgetary woes have humbled the plans of the ESA and Russia. The Obama administration killed its predecessor’s proposal for a new lunar base and scaled down plans for new launch vehicles. Robot landers are still slated to go to Mars but long-term plans to send humans there feel ever vulnerable.

The public and scientists alike have been debating the merits of exploring space with robotic probes rather than humans, mindful of the economic constraints. Recently, Ian A. Crawford of the department of planetary sciences at Birkbeck College in London published a paper in Astronomy and Geophysics (PDF) that argues, contrary to the conventional wisdom, that manned missions yield far more scientific results than robotic ones do. Yet his argument involves some apples-to-oranges comparisons–no one may ever pay for manned missions to all the places that robots can go now–and the prevailing recommendation among space scientists has long been that both types of missions might be essential.

Perhaps the fragile, inconsistent state of space exploration is most painfully obvious in studies of the outer solar system. In 2020 or so, the twin Voyager I and II spacecraft will finally run out of power after more than 40 years of service. During the 1980s and 1990s, their stunning images and measurements offered richly informative details about the outer planets and their moons. Over the past decade, they have also revealed unexpected features in the edge of the so-called heliosphere far beyond Pluto.

Last year, in the Voyager data, Merav Opher of Boston University and her colleagues found evidence for gigantic bubbles of tenuous plasma in what was thought to be a smooth transition between the outward rush of solar wind and the passing current of the interstellar medium. That structure suggests that the magnetic fields in interstellar space and at great distances from the stars that originate them may exert a more powerful influence on the solar system than was believed. Scientists expect that before the Voyagers go black, they will leave the solar system and its heliosphere altogether, giving the human race its first taste of a truly interstellar medium, which might hold lots of surprises.

But those grand successes only set up epic frustrations and failures to come. The magnetic bubble structures in the outer plasma that the Voyagers have detected are very near the threshold of sensitivity for the probes’ magnetometers, so both the existence of these bubbles and the details of their nature are crying out for better instruments. The Voyagers will reach interstellar space, but they will probably die shortly thereafter, so opportunities to taste what lies beyond the solar system will be limited.

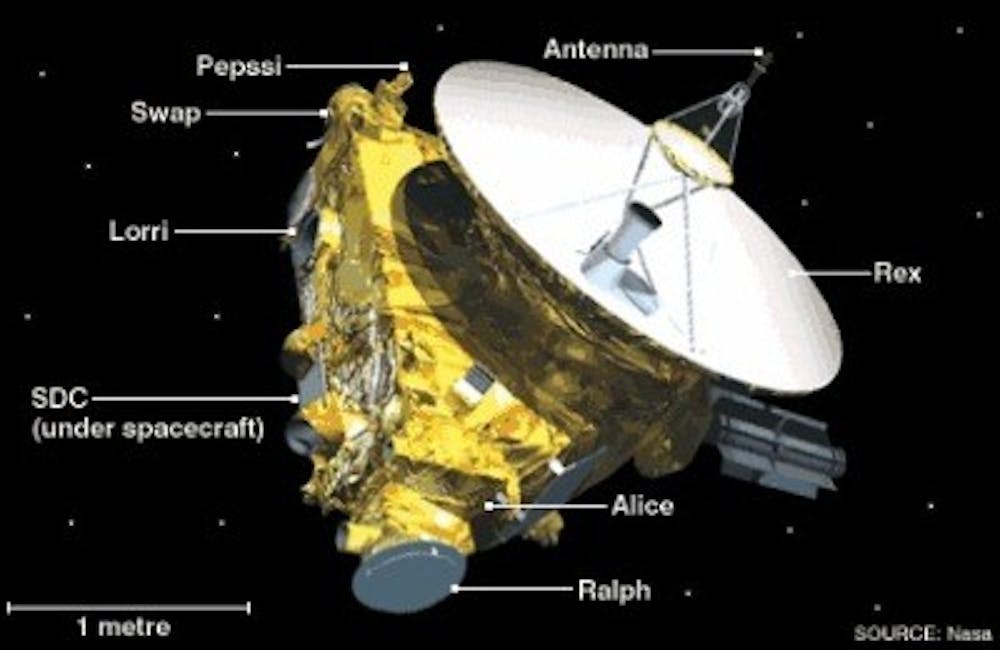

Anyone expecting a new set of spacecraft to solve those mysteries will be in for a long wait. The only probe now similarly en route to the outer solar system is the New Horizons probe launched in 2006, scheduled for a flyby mission to Pluto and its satellite Charon in 2015. Even optimistically, if New Horizons keeps working, it won’t get out to where the Voyagers are now (about 100 times the Earth’s distance from the sun, known as an astronomical unit) until roughly 2039 – 27 years from now. And New Horizons will always trail Voyager 1 because of its trajectory. No other missions to the outer solar system are currently on the docket of NASA or ESA.

Unfortunately, the alignment of the planets has all but foreclosed on the possibility of a speedy follow up. In 2003, NASA entertained ideas for a mission to interstellar space in the Innovative Interstellar Explorer. This small probe (weighing only about 35 kilograms) would have launched in 2014, accelerated on ion thrusters and swung in tight around Jupiter so that it could “slingshot” away at higher speeds. By 2044, it might have been twice as far from the sun as the Voyagers are now – or 200 astronomical units. The launch window only opens once every 12 years.